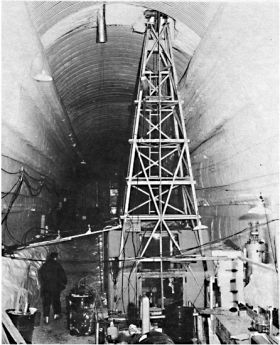

The creation of Camp Century, from the outset, was an audacious scheme. Under the thick ice of Greenland, a scant 800 miles from the North Pole, the US military built a hidden base of ice tunnels, imagined as an extensive network of railway tracks, stretching over 2,500 miles, that would keep 600 nuclear missiles buried under the ice. Construction began in 1959, under cover of a scientific research project, and soon a small installation, powered by a nuclear reactor, nested in the ice sheet.

In the midst of the Cold War, Greenland seemed like a strategic point for the US to stage weapons, ready to attack the USSR. The thick ice sheet, military planners imagined, would provide permanent protection for the base. But after the first tunnels were built, the military discovered that the ice sheet was not as stable as it needed to be: It moved and shifted, destabilizing the tunnels. Within a decade, Camp Century was abandoned.

When siting the secret ice base, the military chose a spot where dry snow kept the surface of Greenland’s ice sheet from melting, and when the base was abandoned its creators expected the remains to stay encased in ice forever. But decades later, conditions have changed, and as a team of researchers reported in a 2016 paper, published in Geophysical Research Letters, the now-melting ice sheet threatens to mobilize the dangerous pollutants left behind.

This hazard-in-waiting is a new kind of environmental threat: In the past, there was little reason to worry about water-borne pollution on an ice sheet 100,000 years old. As Jeff D. Colgan, a professor of political science at Brown University, writes in an article released last week in the journal Global Environmental Politics, Camp Century represents both a second-order environmental threat from climate change and a new path to political conflict.

Read more at Wired

Photo Credit: CRREL Researcher via Wikimedia Commons