Scientists have developed a new technique to examine the effects of chemicals on digestive systems of fish and support research into gut related conditions. It also has potential to reduce the number of animal experiments, in line with the principles of the 3Rs (Reduce, Refine and Replace).

There is a growing scientific, public and regulatory concern about dietary uptake of chemicals. But to implement legislation to assess the toxicity of some chemicals requires thousands of fish and there are currently no reliable alternative methods to assess their accumulation and toxic effects in the gut without using live animals.

Now researchers at the University of Plymouth, working in partnership with pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, have for the first time successfully cultured and maintained cells from the guts of rainbow trout, a recommended fish species for toxicological studies.

They then demonstrated that under laboratory conditions, they could maintain the cells’ function for extended periods while also growing new cells which could be used in future tests to assess the impact of environmental pollutants such as chemicals or plastics which enter in the body via diet.

Read more at University of Plymouth

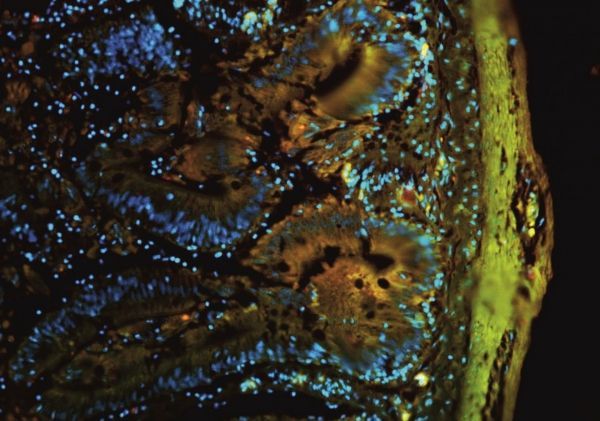

Image: Immunofluorescence of fish intestine organoid: long term culture of intestinal trout tissue shows co-expression of ZO-1 (red), E-cadherin (green) and cell nuclei (blue). CREDIT: University of Plymouth