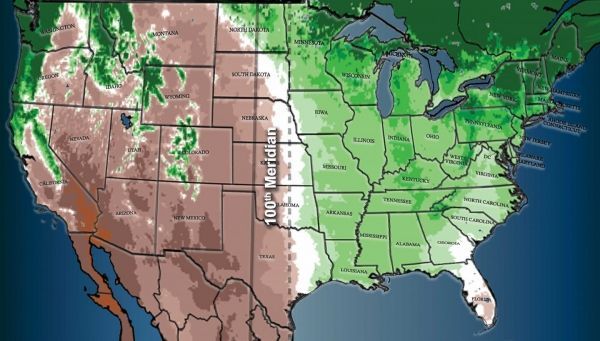

In 1878, the American geologist and explorer John Wesley Powell drew an invisible line in the dirt—a very long line. It was the 100th meridian west, the longitude he identified as the boundary between the humid eastern United States and the arid Western plains. Running south to north, the meridian cuts northward through the eastern states of Mexico, and on to Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, the Dakotas, and the Canadian province of Manitoba on its way to the pole. Powell, best known for exploring the Grand Canyon and other parts of the West, was wary of large-scale settlement in that often harsh region, and tried convincing Congress to lay out water and land-management districts crossing state lines to deal with environmental constraints. Western political leaders hated the idea—they feared this might limit development, and their own power—and it never went anywhere. It was not the first time that politicians would ignore the advice of scientists.

Now, 140 years later, scientists are looking again at the 100th meridian. In two just-published papers, they examine how it has played out in history so far, and what the future may hold. They confirm that the divide has turned out to be very real, as reflected by population and agriculture on opposite sides. They say also that the line appears to be slowly moving eastward, due to climate change. They say it will almost certainly continue shifting in coming decades, expanding the arid climate of the western plains into what we think of as the Midwest. The implications for farming and other pursuits could be huge.

One can literally step over the meridian line on foot, but the boundary it represents is more gradual. In 1890, Powell wrote, “Passing from east to west across this belt a wonderful transformation is observed. On the east a luxuriant growth of grass is seen, and the gaudy flowers of the order Compositae make the prairie landscape beautiful. Passing westward, species after species of luxuriant grass and brilliant flowering plants disappear; the ground gradually becomes naked, with bunch grasses here and there; now and then a thorny cactus is seen, and the yucca plant thrusts out its sharp bayonets.” Today, his description would only partly apply; the “luxuriant grass” of the eastern prairie was long ago plowed under for corn, wheat and other crops, leaving only scraps of the original landscape. The scrubby growth of the thinly populated far western plains remains more intact.

Read more at The Earth Institute at Columbia University

Image: The 100th meridian west (solid line) has long been considered the divide between the relatively moist eastern United States, and the more arid West. Climate change may already have started shifting the divide eastward (dotted line). (Credit: Modified from Seager et al. Earth Interactions, 2018)