A new system devised by MIT engineers could provide a low-cost source of drinking water for parched cities around the world while also cutting power plant operating costs.

About 39 percent of all the fresh water withdrawn from rivers, lakes, and reservoirs in the U.S. is earmarked for the cooling needs of electric power plants that use fossil fuels or nuclear power, and much of that water ends up floating away in clouds of vapor. But the new MIT system could potentially save a substantial fraction of that lost water — and could even become a significant source of clean, safe drinking water for coastal cities where seawater is used to cool local power plants.

The principle behind the new concept is deceptively simple: When air that’s rich in fog is zapped with a beam of electrically charged particles, known as ions, water droplets become electrically charged and thus can be drawn toward a mesh of wires, similar to a window screen, placed in their path. The droplets then collect on that mesh, drain down into a collecting pan, and can be reused in the power plant or sent to a city’s water supply system.

Read more at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

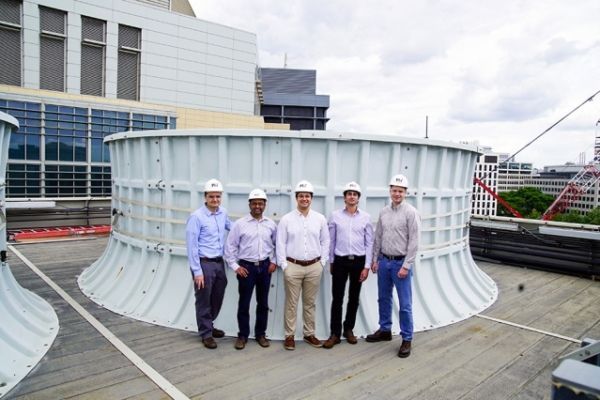

Image: On the roof of the Central Utility Plant building, standing in front of one of the cooling towers, are (left to right): Seth Kinderman, Central Utility Plant engineering manager; Kripa Varanasi, associate professor of mechanical engineering; recent doctoral graduates Karim Khalil and Maher Damak; and Patrick Karalekas, plant engineer, Central Utilities Plant. Credit: Melanie Gonick / MIT