For decades, astronomers have puzzled over the exact source of a peculiar type of faint microwave light emanating from a number of regions across the Milky Way. Known as anomalous microwave emission (AME), this light comes from energy released by rapidly spinning nanoparticles – bits of matter so small that they defy detection by ordinary microscopes. (The period on an average printed page is approximately 500,000 nanometers across.)

“Though we know that some type of particle is responsible for this microwave light, its precise source has been a puzzle since it was first detected nearly 20 years ago,” said Jane Greaves, an astronomer at Cardiff University in Wales and lead author on a paper announcing this result in Nature Astronomy.

Until now, the most likely culprit for this microwave emission was thought to be a class of organic molecules known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) – carbon-based molecules found throughout interstellar space and recognized by the distinct, yet faint infrared (IR) light they emit. Nanodiamonds -- particularly hydrogenated nanodiamonds, those bristling with hydrogen-bearing molecules on their surfaces -- also naturally emit in the infrared portion of the spectrum, but at a different wavelength.

A series of observations with the National Science Foundation’s Green Bank Telescope (GBT) in West Virginia and the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) has -- for the first time -- homed in on three clear sources of AME light, the protoplanetary disks surrounding the young stars known as V892 Tau, HD 97048, and MWC 297. The GBT observed V892 Tau and the ATCA observed the other two systems.

Read more at Green Bank Observatory

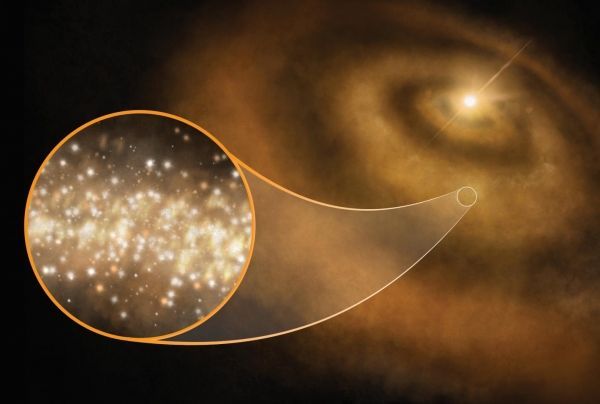

Image: This is an artist impression of nanoscale diamonds surrounding a young star in the Milky Way. Recent GBT and ATCA observations have identified the telltale radio signal of diamond dust around 3 such stars, suggesting they are a source of the so-called anomalous microwave emission. (Credit: S. Dagnello, NRAO/AUI/NSF)