Climate scientists have not been properly accounting for what plants do at night, and that, it turns out, is a mistake. A new study from the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has found that plant nutrient uptake in the absence of photosynthesis affects greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere.

In a study published today in Nature Climate Change, lead author William Riley demonstrates how to improve climate models to more accurately represent land biogeochemical dynamics. Using a new global land model they developed and integrated in DOE’s Energy Exascale Earth System Model (E3SM), Riley and his team found that plants can uptake more carbon dioxide and soils lose less nitrous oxide than previously thought. Their global simulations imply weaker terrestrial ecosystem feedbacks with the atmosphere than current models predict.

“This is goodish news, with respect to what is currently in the climate models,” said Riley, a scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Earth & Environmental Sciences Area. “But it’s not good news in general – it’s not going to solve the problem. No matter what, plants will not keep up with anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions; it’s just that they might do better than current models suggest.”

Humans have emitted a record-setting 34 gigatons of CO2 per year, averaged over the past decade. Roughly half of that remains in the atmosphere, while the rest is absorbed by oceans and land (through photosynthesis); the latter amount, called the terrestrial carbon sink, varies year to year depending on factors such as fires, drought, land use, and weather.

Read more at DOE/Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

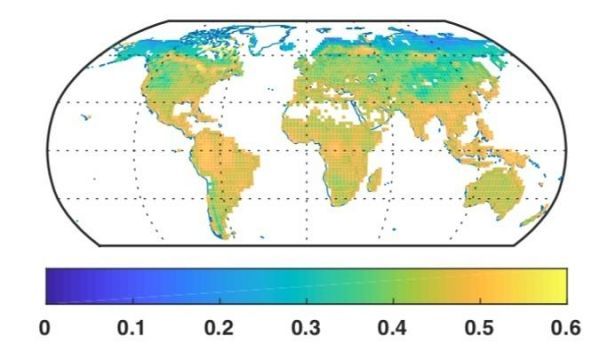

Image: Photosynthesis-inactive period nutrient uptake is a large proportion of annual uptake globally. This map shows the fraction of annual plant nitrogen uptake that occurs during photosynthesis-inactive periods. (Credit: Berkeley Lab)