Look at a digital map of the world with pixels that are more than 50 miles on a side and you’ll see a hazy picture: whole cities swallowed up into a single dot; Vancouver Island and the Great Lakes just one pixel wide. You won’t see farmer’s fields, or patches of forest, or clouds. Yet this is the view that many climate models have of our planet when trying to see centuries into the future, because that’s all the detail that computers can handle. Turn up the resolution knob and even massive supercomputers grind to a slow crawl. “You’d just be waiting for the results for way too long; years probably,” says Michael Pritchard, a next-generation climate modeler at the University of California, Irvine. “And no one else would get to use the supercomputer.”

The problem isn’t just academic: It means we have a blurry view of the future. It is hard to know if, importantly, a warmer world will bring more low-lying clouds that shield Earth from the sun, cooling the planet, or fewer of them, warming it up. For this reason and more, the roughly 20 models run for the last assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) disagree with each other profoundly: Double the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and one model says we’ll see a 1.5 degree Celsius bump; another says it will be 4.5 degrees C. “It’s super annoying,” Pritchard says. That factor of three is huge — it could make all the difference to people living on flooding coastlines or trying to grow crops in semi-arid lands.

Pritchard and a small group of other climate modelers are now trying to address the problem by improving models with artificial intelligence. (Pritchard and his colleagues affectionately call their AI system the “Cloud Brain.”) Not only is AI smart; it’s efficient. And that, for climate modelers, might make all the difference.

Read more at Yale Environment 360

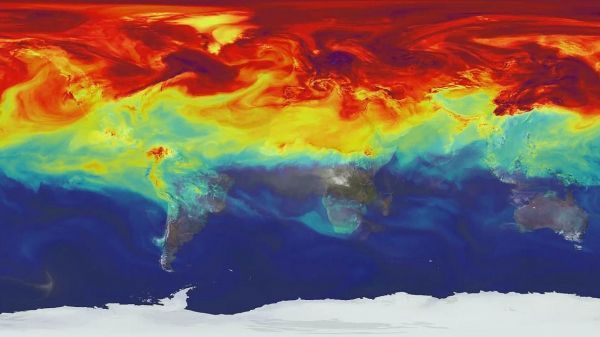

Image: A computer simulation of carbon dioxide movement in the atmosphere. (Credit: NASA)