Over the last million years, ice ages have intensified and lengthened. According to a study led by the University of Bern, this previously unexplained climate transition coincides with a diminution of the mixing between deep and surface waters in the Southern Ocean.

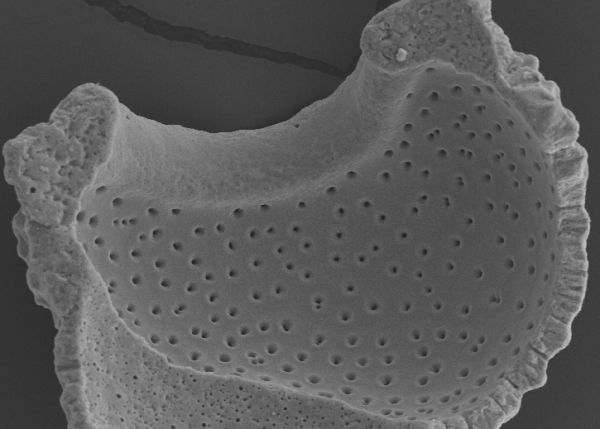

An analysis of marine sediments collected at a depth of more than 2 km has just provided an answer to one of the riddles of the earth’s climate history: the mid-Pleistocene transition, which began around one million years ago. Thereafter, ice ages lengthened and intensified, and the frequency of their cycles increased from 40,000 years to 100,000 years. The study, which appeared in the journal Science, shows one of the keys to this phenomenon lies in the deep waters of the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica.

Ocean waters contain 60 times more carbon than the atmosphere. Consequently, small variations in the carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration of the waters play a major role in climate transitions. Led by Samuel Jaccard, SNSF Professor at the University of Bern, the new study traced the evolution of mixing between deep and surface waters in the Southern Ocean. Mixing is a major factor in the global climate system, because it brings oceanic CO2 to the surface, where it escapes into the atmosphere.

The findings show that mixing was significantly reduced at the end of the Mid-Pleistocene Transition, about 600,000 years ago. Moreover, they explain how the reduced mixing diminished the amount of CO2 released by the ocean, which in turn reduced the greenhouse effect and intensified ice ages. The study thus sheds light on feedback mechanisms capable of significantly slowing or accelerating ongoing climate change.

Continue reading at Universitat Bern

Image via Universitat Bern