Drawing design inspiration from the skin of stealthy sea creatures, engineers at the University of California, Irvine have developed a next-generation, adaptive space blanket that gives users the ability to control their temperature. The innovation is detailed in a study published today in Nature Communications.

“Ultra-lightweight space blankets have been around for decades – you see marathon runners wrapping themselves in them to prevent the loss of body heat after a race – but the key drawback is that the material is static,” said co-author Alon Gorodetsky, UCI associate professor of chemical & biomolecular engineering. “We’ve made a version with changeable properties so you can regulate how much heat is trapped or released.”

The UCI researchers took design cues from various species of squids, octopuses and cuttlefish that use their adaptive, dynamic skin to thrive in aquatic environments. A cephalopod’s unique ability to camouflage itself by rapidly changing color is due, in part, to skin cells called chromatophores that can instantly change from minute points to flattened disks.

“We use a similar concept in our work, where we have a layer of these tiny metal ‘islands’ that border each other,” said lead author Erica Leung, a UCI graduate student in chemical & biomolecular engineering. “In the relaxed state, the islands are bunched together and the material reflects and traps heat, like a traditional Mylar space blanket. When the material is stretched, the islands spread apart, allowing infrared radiation to go through and heat to escape.”

Read more at University of California - Irvine

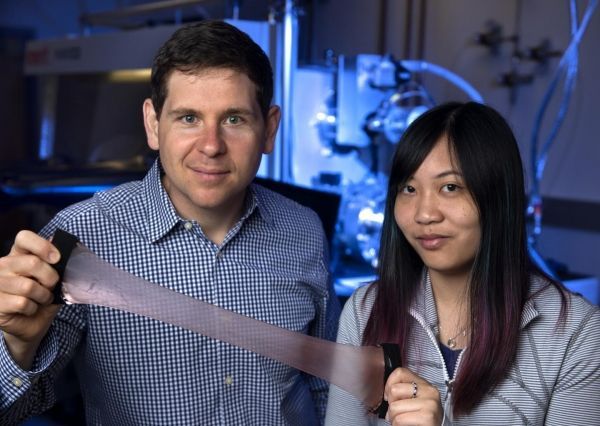

Image: Alon Gorodetsky, UCI associate professor of chemical & biomolecular engineering, and Erica Leung, a UCI graduate student in that department, have invented a new material that can trap or release heat as desired. (Credit: Steve Zylius / UCI)