Detection of a supernova with an unusual chemical signature by a team of astronomers led by Carnegie’s Juna Kollmeier—and including Carnegie’s Nidia Morrell, Anthony Piro, Mark Phillips, and Josh Simon—may hold the key to solving the longstanding mystery that is the source of these violent explosions. Observations taken by the Magellan telescopes at Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile were crucial to detecting the emission of hydrogen that makes this supernova, called ASASSN-18tb, so distinctive.

Their work is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Type Ia supernovae play a crucial role in helping astronomers understand the universe. Their brilliance allows them to be seen across great distances and to be used as cosmic mile-markers, which garnered the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics. Furthermore, their violent explosions synthesize many of the elements that make up the world around us, which are ejected into the galaxy to generate future stars and stellar systems.

Although hydrogen is the most-abundant element in the universe, it is almost never seen in Type Ia supernova explosions. In fact, the lack of hydrogen is one of the defining features of this category of supernovae and is thought to be a key clue to understanding what came before their explosions. This is why seeing hydrogen emissions coming from this supernova was so surprising.

Read more at Carnegie Institution for Science

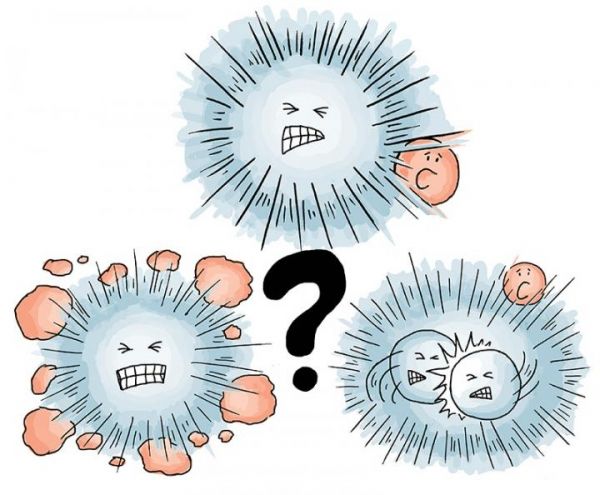

Image: This cartoon courtesy of Anthony Piro illustrates three possibilities for the origin of the mysterious hydrogen emissions from the Type IA supernova called ASASSN-18tb that were observed by the Carnegie astronomers. Starting from the top and going clockwise: The collision of the explosion with a hydrogen-rich companion star, the explosion triggered by two colliding white dwarf stars subsequently colliding with a third hydrogen-rich star, or the explosion interacting with circumstellar hydrogen material. (Credit: Courtesy of Anthony Piro, Carnegie Institution for Science)