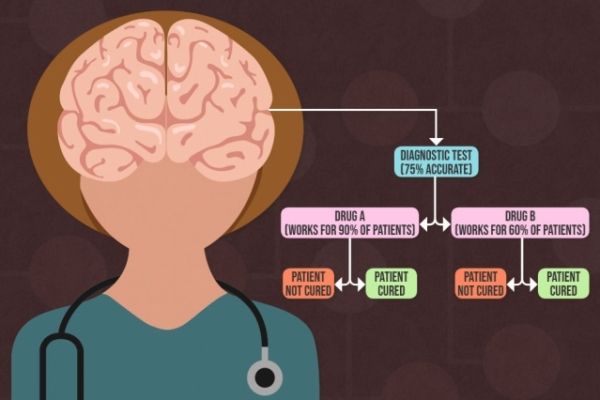

When making a complex decision, we often break the problem down into a series of smaller decisions. For example, when deciding how to treat a patient, a doctor may go through a hierarchy of steps — choosing a diagnostic test, interpreting the results, and then prescribing a medication.

Making hierarchical decisions is straightforward when the sequence of choices leads to the desired outcome. But when the result is unfavorable, it can be tough to decipher what went wrong. For example, if a patient doesn’t improve after treatment, there are many possible reasons why: Maybe the diagnostic test is accurate only 75 percent of the time, or perhaps the medication only works for 50 percent of the patients. To decide what do to next, the doctor must take these probabilities into account.

In a new study, MIT neuroscientists explored how the brain reasons about probable causes of failure after a hierarchy of decisions. They discovered that the brain performs two computations using a distributed network of areas in the frontal cortex. First, the brain computes confidence over the outcome of each decision to figure out the most likely cause of a failure, and second, when it is not easy to discern the cause, the brain makes additional attempts to gain more confidence.

Read more at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Image: MIT neuroscientists are exploring how the brain handles hierarchical decision-making processes that involve breaking down a larger decision into smaller ones that each carry a degree of uncertainty. CREDIT: Chelsea Turner, MIT