A newly developed technique that shows artery clogging fat-and-protein complexes in live fish gave investigators from Carnegie, Johns Hopkins University, and the Mayo Clinic a glimpse of how to study heart disease in action. Their research, which is currently being used to find new drugs to fight cardiovascular disease, is now published in Nature Communications.

Fat molecules, also called lipids, such as cholesterol and triglycerides are shuttled around the circulatory system by a protein called Apolipoprotein-B, or ApoB for short. These complexes of lipid and protein are called lipoproteins but may be more commonly known as “bad cholesterol.”

Sometimes this fat-and-cholesterol ferrying apparatus stops in its tracks and embeds itself in the sides of blood vessels, forming a dangerous buildup. Called plaque, these deposits stiffen the wall of an artery and makes it more difficult for the heart to pump blood, which can eventually lead to a heart attack.

“These ApoB-containing lipoproteins are directly responsible for creating plaques in blood vessels, so learning more about them is essential to fighting the global epidemic of cardiovascular disease,” explained lead author James Thierer a graduate student at Johns Hopkins who does research at Carnegie’s Department of Embryology.

Read more at: Carnegie Institution for Science

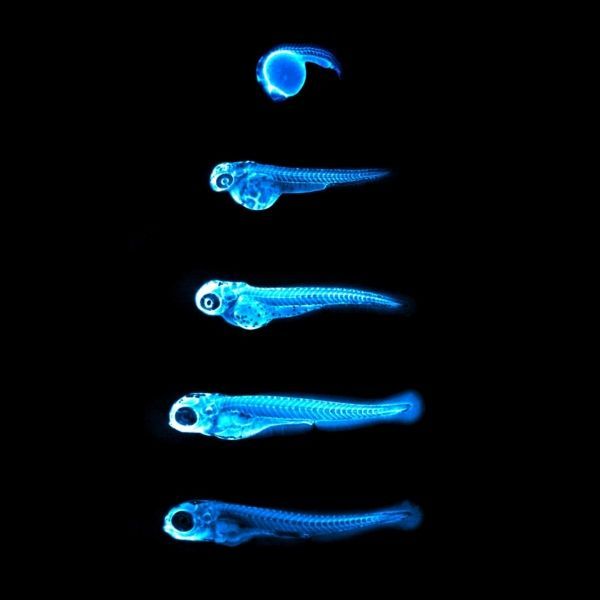

This image captures the bright blue light (chemiluminescence) emitted by the NanoLuc protein in LipoGlo zebrafish. By attaching this glowing enzyme to bad-cholesterol particles, researchers are able to visualize how much cholesterol is present in each fish, and where in the body it resides. The top image shows a zebrafish embryo 24 hours into development, with many cholesterol particles emanating from its large spherical yolk. Subsequent images were taken every 24 hours, showing that cholesterol levels peak between three and four days of age in zebrafish embryos. (Photo Credit: The image is provided courtesy of James Thierer and Ed Hirschmugl)