We receive half of our genes from each biological parent, so there’s no avoiding inheriting a blend of characteristics from both. Yet, for single-celled organisms like bacteria that reproduce by splitting into two identical cells, injecting variety into the gene pool isn’t so easy. Random mutations add some diversity, but there’s a much faster way for bacteria to reshuffle their genes and confer evolutionary advantages like antibiotic resistance or pathogenicity.

Known as horizontal gene transfer, this process permits bacteria to pass pieces of DNA to their peers, in some cases allowing those genes to be integrated into the recipient’s genome and passed down to the next generation.

The Grossman lab in the MIT Department of Biology studies one class of mobile DNA, known as integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs). While ICEs contain genes that can be beneficial to the recipient bacterium, there’s also a catch — receiving a duplicate copy of an ICE is wasteful, and possibly lethal. The biologists recently uncovered a new system by which one particular ICE, ICEBs1, blocks a donor bacterium from delivering a second, potentially deadly copy.

Read more at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

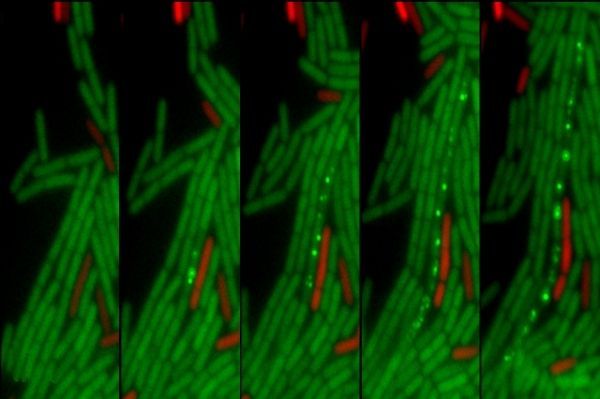

Photo: The Grossman lab studies the mobile genetic element ICEBs1, which is shown here being transferred from red donor cells to green recipient cells that display fluorescent dots after transfer. CREDIT: Babic et al./American Society for Microbiology