The water crisis in Flint, Michigan — which began in 2014 but to this day has not been completely resolved — brought the public health and economic costs of lead exposure into sharp focus. The crisis sparked conversations about environmental justice and raised awareness about the impacts of lead in water in particular.

But water isn't the only way people can be exposed to dangerous levels of lead. Carnegie Mellon University's Karen Clay warns that lead-contaminated air and topsoil pose serious health risks as well. It's important to be aware of personal exposure, because lead can cause negative health outcomes such as reduced fertility in adults and cognitive difficulties in young boys.

"When you're thinking about impacts on children, we don't have systematic data on the characteristics of these kids," said Clay, a professor of economics and public policy in the Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy and the Tepper School of Business. "Yes, blood lead levels are collected for children, but not all children get tested. You need pediatricians who are thinking about this and willing to encourage parents to get their kids tested. And even then, sometimes the parents won't get the testing."

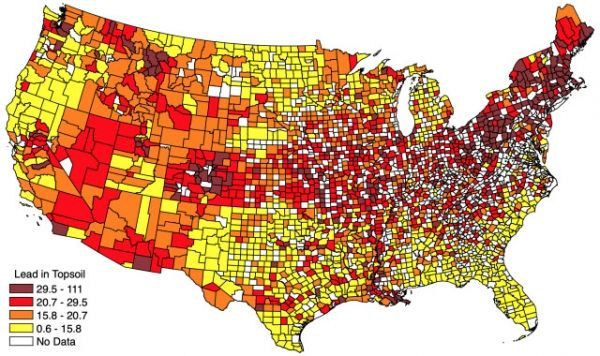

Clay conducted research with colleagues Edson Severnini and Magarita Portnykh. The team looked at data related to lead levels in soil, which still remain in many parts of the United States following the ramp down of leaded gasoline. Lead in soil can be resurfaced by human activity and can become airborne in some cases. For example, walking over a patch of contaminated soil — or a child playing in dirt — can re-suspend lead in the air. Lead also can settle on clothing and the skin and be tracked into households.

Continue reading at Carnegie Mellon University

Image via Carnegie Mellon University