Bacteria are becoming increasingly resistant to common antibiotics. Often, resistance is mediated by resistance genes, which can simply jump from one bacterial population to the next. It’s a common assumption that the resistance genes spread primarily when antibiotics are used, a rationale backed up by Darwin’s theory: only in cases where antibiotics are actually being used does a resistant bacterium have an advantage over other bacteria. In an antibiotic-free environment, resistant bacteria have no advantage. This explains why health experts are concerned about the excessive use of antibiotics and call for more restrictions on their use.

However, a team of researchers led by scientists from ETH Zurich and the University of Basel have now discovered an additional, previously unknown mechanism that spreads resistance in intestinal bacteria that is independent of the use of antibiotics. “Restricting the use of antibiotics is important and the indeed the right thing to do, but this measure alone is not sufficient to prevent the spread of resistance,” says Médéric Diard, who until recently held a post at ETH Zurich and is now a professor at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel. He continues, “If you want to control the spread of resistance genes, you have to start with the resistant microorganisms themselves and prevent these from spreading through, say, more effective hygiene measures or vaccinations.” Diard led the research project together with Wolf-Dietrich Hardt, Professor for Microbiology at ETH Zurich.

Read more at ETH Zurich

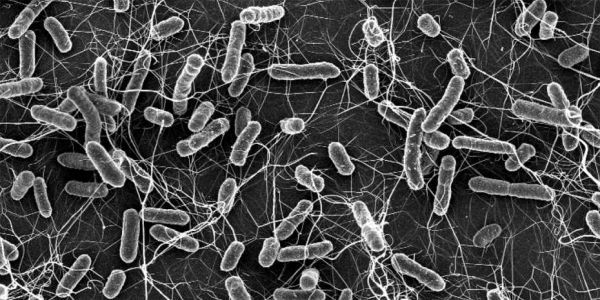

Photo: Salmonella causes diarrhoea in animals and humans. These bacteria become a particular public health concern if they are resistant to antibiotics (electron microscopic photograph). (Credit: ETH Zurich / Stefan Fattinger)