Diversity – at least among cancer cells – is not a good thing. Weizmann Institute of Science research shows that in melanoma, tumors with cells that have differentiated into more diverse subtypes are less likely to be affected by the immune system, thus reducing the chance that immunotherapy will be effective. The findings of this research, which were published today in Cell, may provide better tools for designing personalized protocols for cancer patients, as well as pointing toward new avenues of research into anti-cancer vaccines.

Prof. Yardena Samuels of the Institute’s Molecular Cell Biology Department wanted to know why, despite the fact that cancer deaths from melanoma have dropped in recent years thanks to new immunotherapy treatments, many patients do not respond to the therapy. The reasons for this have not been clear, though the leading hypothesis, supported by a few studies, has been that tumors with more mutations – a higher “tumor mutational burden” -- are more likely to respond to immunotherapy. Some patients even spend large sums to undergo radiation or chemical treatments to increase tumor mutations, but a causal relationship between the two has not yet been proven. Samuels and her colleagues were intrigued by studies that had suggested a different possible correlation – that between heterogeneity (that is, the genetic diversity among tumor cells) and the response to therapy. To investigate this theory, however, the team had to develop a new experimental system to check exactly which factors play a role.

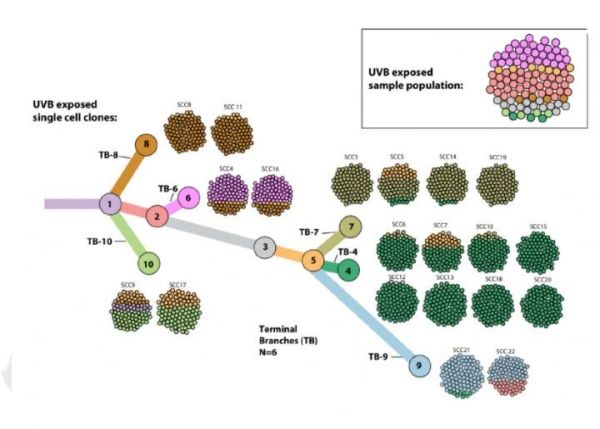

In the study, which was led by Drs. Yochai Wolf and Osnat Bartok in Samuels’ lab, the researchers took mouse melanoma cells and exposed them to a type of UV light known to promote this cancer. This increased both the mutations and the cell heterogeneity in the growth. When they injected mice with either these cells or the regular melanoma cells, the irradiated ones multiplied faster and were more aggressive. Despite the fact that these cells had a higher mutational burden – and thus should have been more responsive to immunotherapy – they actually were less likely to be eradicated than those from the original tumor. In other words, although there was a high mutational burden, there was also high heterogeneity, and the researchers hypothesized that the latter was driving the resistance.

Read more at Weizmann Institute of Science

Image: Tumor cells were mapped to a phylogenetic tree according to heterogeneity, enabling the researchers to conduct further experiments (Credit: Weizmann Institute of Science)