An international research team led by Giuseppe Marramà from the Institute of Paleontology of the University of Vienna discovered a new and well-preserved fossil stingray with an exceptional anatomy, which greatly differs from living species. The find provides new insights into the evolution of these animals and sheds light on the recovery of marine ecosystems after the mass extinction occurred 66 million years ago. The study was recently published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Stingrays (Myliobatiformes) are a very diverse group of cartilaginous fishes which are known for their venomous and serrated tail stings, which they use against other predatory fish, and occasionally against humans. These rays have a rounded or wing-like pectoral disc and a long, whip-like tail that carries one or more serrated and venomous stings. The stingrays include the biggest rays of the world like the gigantic manta rays, which can reach a “wingspan” of up to seven meters and a weight of about three tons.

Fossil remains of stingrays are very common, especially their isolated teeth. Complete skeletons, however, exist only from a few extinct species coming from particular fossiliferous sites. Among these, Monte Bolca, in northeastern Italy, is one of the best known. So far, more than 230 species of fishes have been discovered that document a tropical marine coastal environment associated with coral reefs which dates back to about 50 million years ago in the period called Eocene.

Read more at University of Vienna

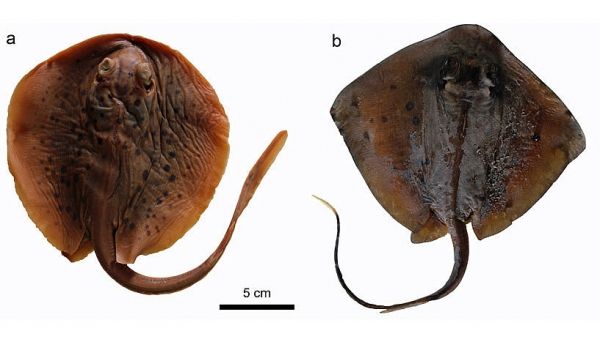

Image: Two living stingrays: a) Taeniura lymma; b) Neotrygon sp. The specimens are in the collection of the Institute of Paleontology of the University of Vienna. CREDIT: Giuseppe Marramà