Upside-down “rivers” of warm ocean water are eroding the fractured edges of thick, floating Antarctic ice shelves from below, helping to create conditions that lead to ice-shelf breakup and sea-level rise, according to a new study.

The findings, published today in Science Advances, describe a new process important to the future of Antarctica’s ice and the continent’s contribution to rising seas. Models and forecasts do not yet account for the newly understood and troubling scenario, which is already underway.

“Warm water circulation is attacking the undersides of these ice shelves at their most vulnerable points,” said Alley, who earned her Ph.D. at the University of Colorado Boulder, in the National Snow and Ice Data Center, part of CIRES. Alley is now a visiting assistant professor of Earth Sciences at The College of Wooster in Ohio. “These effects matter,” she said. “But exactly how much, we don’t yet know. We need to.”

Ice shelves float out on the ocean at the edges of land-based ice sheets, and about three-quarters of the Antarctic continent is surrounded by these extensions of the ice sheet. The shelves can be hemmed in by canyon-like walls and bumps in the ocean floor. When restrained by these bedrock obstructions, ice shelves slow down the flow of ice from the interior of the continent toward the ocean. But if an ice shelf retreats or falls apart, ice on land flows much more quickly into the ocean, increasing rates of sea-level rise.

Continue reading at Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences

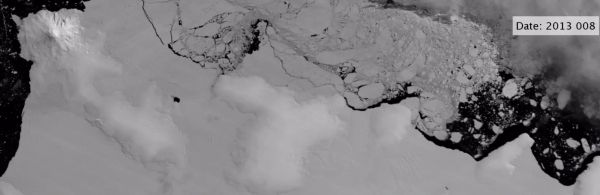

Image via Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences