When clouds loft tropical air masses higher in the atmosphere, that air can carry up gases that form into tiny particles, starting a process that may end up brightening lower-level clouds, according to a CIRES-led study published today in Nature. Clouds alter Earth’s radiative balance, and ultimately climate, depending on how bright they are. And the new paper describes a process that may occur over 40 percent of the Earth’s surface, which may mean today's climate models underestimate the cooling impact of some clouds.

“Understanding how these particles form and contribute to cloud properties in the tropics will help us better represent clouds in climate models and improve those models,” said Christina Williamson, a CIRES scientist working in NOAA ESRL’s Chemical Sciences Division and the paper’s lead author. The research team mapped out how these particles form using measurements from one of the largest and longest airborne studies of the atmosphere, a field campaign that spanned the Arctic to the Antarctic over a three-year period.

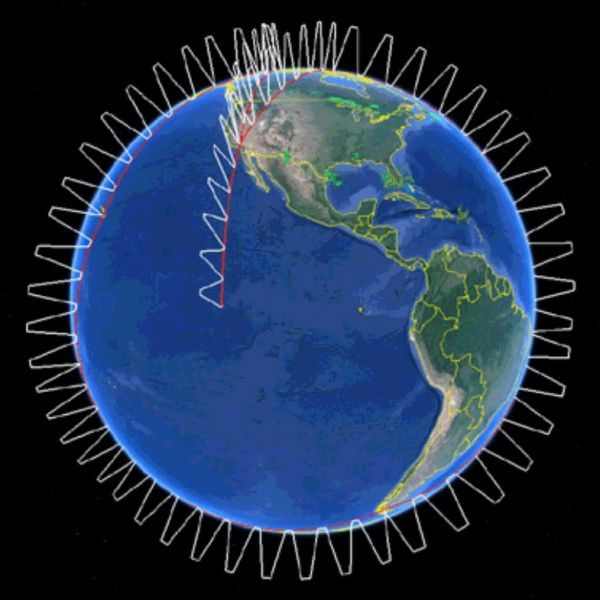

Williamson and her colleagues, from CIRES, CU Boulder, NOAA and other institutions, including CIRES scientist Jose Jimenez, took global measurements of aerosol particles as part of the NASA Atmospheric Tomography Mission, or ATom. During ATom, a fully instrumented NASA DC-8 aircraft flew four pole-to-pole deployments—each one consisting of many flights over a 26-day period—over the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans in every season. The plane flew from near sea level to an altitude of about 12 km, continuously measuring greenhouse gases, other trace gases and aerosols.

Continue reading at Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences

Image via Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences