The findings suggest that these boggy areas play a more important role in climate change and the carbon cycle than they’re typically given credit for.

Peatlands are damp, mossy landscapes built on layers of partially decayed plants. Because the plant matter doesn’t fully break down, peat can end up storing large amounts of carbon for thousands of years — much longer than a typical forest. Yet global climate models, which scientists use to predict climate change and its impacts, rarely account for the carbon that peat and other soils absorb, store and release.

“The carbon that’s underground is the least well understood pool of carbon,” said lead author Jonathan Nichols, an associate research professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Continue reading at Columbia University Earth Institute

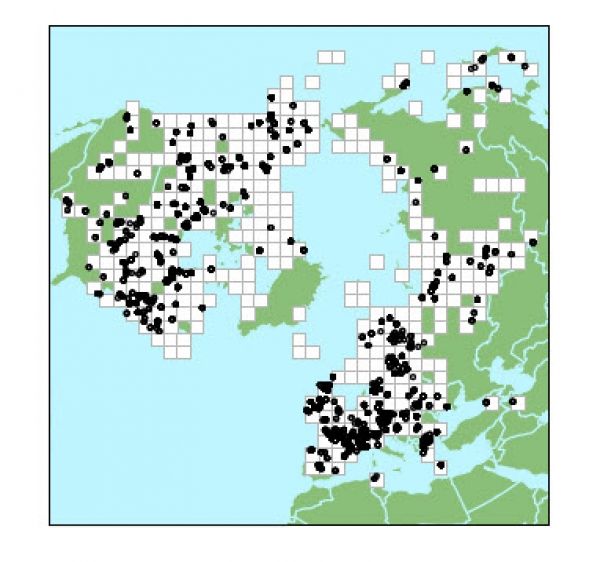

Image via Columbia University Earth Institute