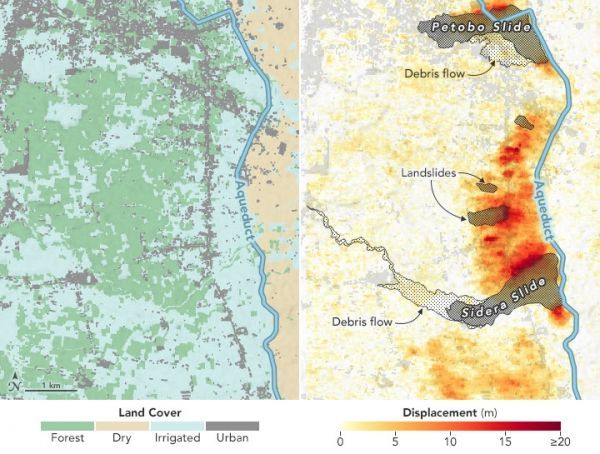

On September 28, 2018, a powerful, shallow earthquake ruptured the land surface and seafloor near Indonesia’s Sulawesi island and sent a devastating tsunami into the city of Palu. While the nearby strike-slip fault was a known tsunami hazard, the magnitude 7.5 earthquake surprised scientists because it triggered large and deadly landslides in an area with a gently sloping landscape.

One year later, a team of scientists from six countries has unraveled the mystery of the landslides and discovered a new earthquake hazard in the process. Examining various types of radar and visible satellite data, the team found that mud and soil flowed most readily near irrigated rice paddies.

The practice of keeping farmland soaked for rice cultivation slowly draws the water table—the layer below ground where the soil becomes saturated—closer to the land surface. This makes the soil wetter and more prone to liquefaction—the process by which sandy soils behave like a liquid in response to strong ground shaking. As shaking overpowers the friction that normally holds particles together, soil loses its structural integrity and begins to flow like a liquid. It can act like a lubricated surface, allowing relatively solid ground to slide freely downslope under the force of gravity.

Continue reading at NASA Earth Observatory

Image via NASA Earth Observatory