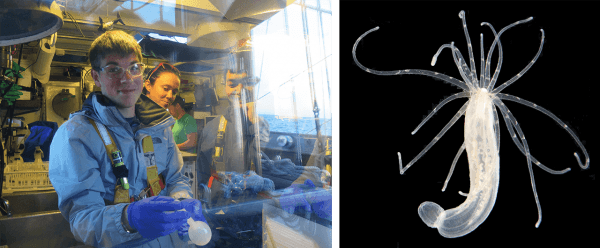

For humans, light is a strong environmental time cue that keeps our body clocks in sync and help regulate sleep and wakefulness over a 24-hour period. But it turns out, light also engages the internal clocks of Nematostella vectensis—inchworm-sized sea anemones that live in marshes on Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

These anemones are nocturnal and are known to get their wiggle on when it's dark. But what happens when temperature—not light—changes over the course of a full day spent in the muck? Does their 24-hour rhythm get disrupted? And how do temperature changes affect their physiology over daily or tidal periods?

These are some of the questions that keep Cory Berger, an MIT-WHOI Joint Program student, up at night.

“No one has looked at this before,” says Berger, who works with populations of Nematostella originally collected from Great Sippewissett Marsh, a large tidal salt marsh that sits behind two barrier beaches along Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts. “One of the reasons we care about this species is because it’s in the Cnidaria phylum—the same group of animals as corals—and we know very little about the influence of temperature on coral circadian cycles. Nematostella is a model we can use to learn more about animals like corals that are harder to keep in the lab.”

Read more at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Image: Left: MIT-WHOI Joint Program student Cory Berger prepares water samples on Sea Education Assocation’s (SEA) sailing vessel, the SSV Corwith Cramer. (Photo courtesy of Laura Heinen, SEA) Right: Nematostella vectensis is a nocturnal sea anemone species that lives in salt marshes along the east coast of the United States. (Photo courtesy of Smithsonian Environmental Research Center)