In the popular book The Demon in the Machine, physicist Paul Davies argues that what’s missing in the definition of life is how biological processes create “information,” and such information storage is the stuff of life, like a bird’s ability to navigate or a human’s ability to solve complex problems. The “Demon” Davies refers to is Maxwell’s Demon, as proposed by 19th century physicist James Clerk Maxwell as a thought experiment. Maxwell’s hypothetical “demon” controls a gate between two chambers of gas and knows when to open the gate only to allow gas molecules moving faster than average to pass through it. This way, a chamber could be heated and create “energy” to be put to work. Such a demon would amount to a workaround of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. And that, as we know, is impossible. We also know, of course, that demons don’t exist.

However, living things use many protein devices called enzymes that mimic such a demon each time a muscle contracts or when any chemical reaction needs to be driven uphill and away from thermodynamic equilibrium like the gas molecules chosen by the demon. How these dynamic machines work has long been puzzling. Over the past 75 years, scientists have chipped away at this problem without identifying precise details of how any of these enzyme machines accomplishes the sleight of hand that sustains living things, such as humans who live in a chemical state far from equilibrium.

For the first time, in a paper published in Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics by Charlie Carter, PhD, professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the UNC School of Medicine, and supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, describes the details that enable one such machine to work like Maxwell’s demon.

Read more at University Of North Carolina

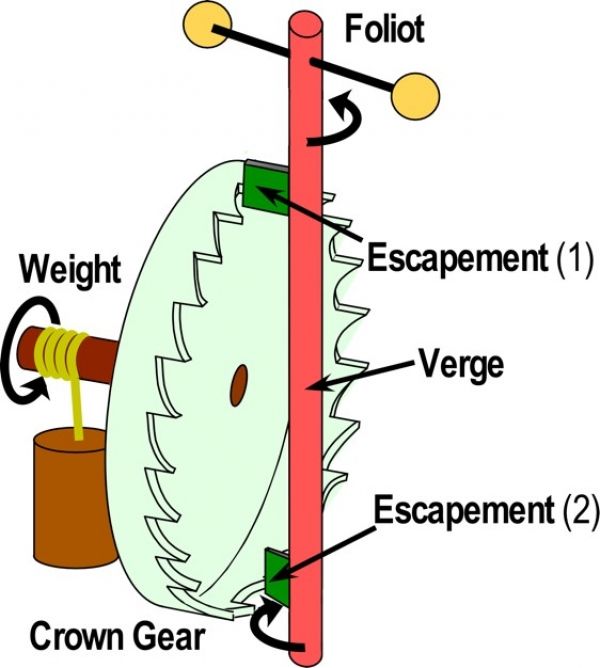

Image: Escapement mechanisms of clocks as a metaphor for protein function like Maxwell’s demons. The Foliot swings back and forth like the pendulum in a clock. The essential features enabling time keeping are labeled. The central function of an escapement is illustrated by the two dark green blades that control the advance of the crown gear in a mechanical clock. CREDIT: University Of North Carolina