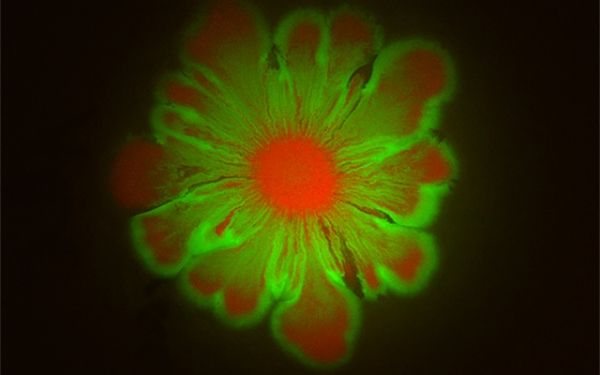

Microbial communities inhabit every ecosystem on Earth, from soil to rivers to the human gut. While monoclonal cultures often exist in labs, in the real world, many different microbial species inhabit the same space. Researchers at University of California San Diego have discovered that when certain microbes pair up, stunning floral patterns emerge.

In a paper published in a recent issue of eLife, a team of researchers at UC San Diego’s BioCircuits Institute (BCI) and Department of Physics, led by Research Scientist and BCI Associate Director Lev Tsimring, reports that when non-motile E. coli (Escherichia coli) are placed on an agar surface together with motile A. baylyi (Acinetobacter baylyi), the E. coli “catch a wave” at the front of expanding A. baylyi colony.

The agar provided food for the bacteria and also a surface on which E. coli couldn’t easily move (making it non-motile). A. baylyi, on the other hand, can crawl readily across the agar using microscopic legs called pili. Thus, a droplet of pure E. coli would barely spread over a 24-hour period, while a droplet of pure A. baylyi would cover the entire area of the petri dish.

Read more at University of California - San Diego

Image Credit: BioCircuits Institute/UC San Diego