Water layering is intensifying significantly in about 40% of the world's oceans, which could have an impact on the marine food chain. The finding, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, could be linked to global warming.

Tohoku University geophysicist Toshio Suga collaborated with climate physicist Ryohei Yamaguchi of Korea's Pusan National University to investigate how upper-ocean stratification has changed over a period of 60 years.

Upper-ocean stratification is the presence of water layers of varying densities scattered between the ocean's surface and a depth of 200 metres. Density describes how tightly water is packed within a given volume and is affected by water temperature, salinity and depth. More dense water layers lie beneath less dense ones.

Ocean water density plays a vital role in ocean currents, heat circulation, and in bringing vital nutrients to the surface from deeper waters. The more significant the stratification in the upper ocean, the larger the barrier between the relatively warm, nutrient-depleted surface, and the relatively cool, nutrient-rich, deeper waters. More intense stratification could mean that microscopic photosynthetic organisms called phytoplankton that live near the ocean's surface won't get the nutrients they need to survive, affecting the rest of the marine food chain.

Read more at Tohoku University

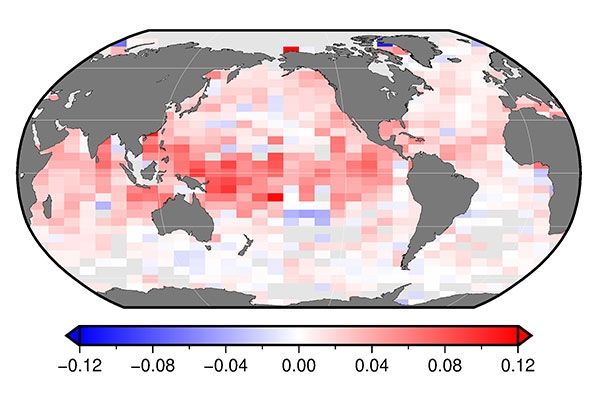

Image: Upper ocean stratification has been strengthening in a large part of the global ocean since the 1960s. Color shows trends in density difference between the surface and 200-m depth (unit: kg m-3/decade). Image Credit: Ryohei Yamaguchi