Due to Zika virus, more than 1,600 babies were born in Brazil with microcephaly, or abnormally small heads, from September 2015 through April 2016. The epidemic took health professionals by surprise because the virus had been known since 1947 and was not linked to birth defects.

As scientists scrambled to figure out what was going on, one fact stood out: 83% of microcephaly cases came from northeastern Brazil, even though Zika infections were recorded nationwide.

Researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis since have learned that the strain of virus circulating in the northeastern Brazilian state of Paraíba in 2015 was particularly damaging to the developing brain. Kevin Noguchi, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and the study’s senior author, spoke about the findings, which are available online in The Journal of Neuroscience.

Read more at Washington University School of Medicine

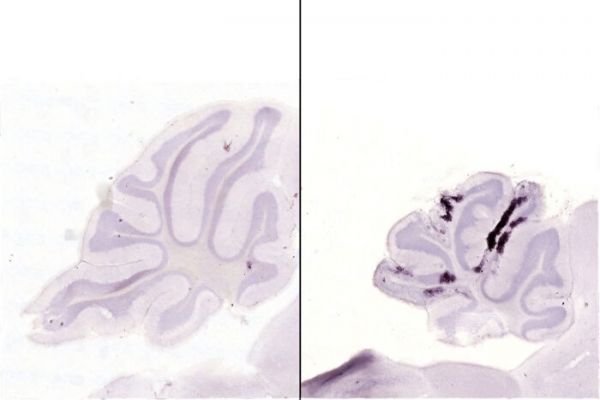

Image: Dark purple spots in the images of mouse brains indicate dying neurons. The brain of a mouse infected with a strain of Zika virus from Brazil (right) is shrunken and has more dying cells compared with that of a mouse infected with a strain from French Polynesia (left). Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that the strain of Zika that circulated in Brazil during the microcephaly epidemic that began in 2015 was particularly damaging to the developing brain. CREDIT: KEVIN NOGUCHI