During past glacial periods the earth was about 6ºC colder and the Northern hemisphere continents were covered by ice sheets up to 4 kilometers thick. However, the earth would not have been so cold, nor the ice sheets so immense, if it were not for the effects of sea ice on the other side of planet.

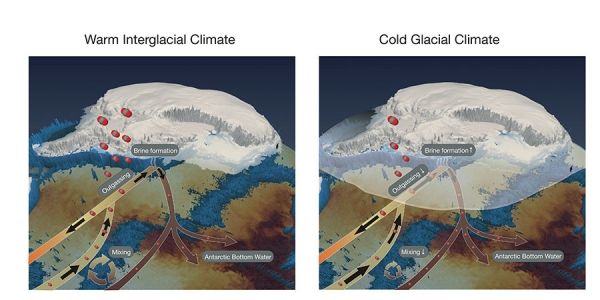

This is the conclusion of a study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America by a team of scientists from the IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP) in Busan, South Korea and the University of Hawaii at Manoa, in Honolulu, HI, USA. In the study, the scientists investigated what role sea ice (frozen ocean water) in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antartica played in past climate transitions. They found that under glacial conditions sea ice not only inhibits outgassing of carbon dioxide from the surface ocean to the atmosphere, but it also increases storage of carbon in the deep ocean. These processes lock away extra carbon in the ocean that would otherwise escape to the atmosphere as CO2, warm the planet, and reduce glacial amplitudes.

We know from air bubbles trapped in ice cores that the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere during cold glacial periods was 80-100 parts per million (ppm) lower than the pre-industrial levels (280 ppm). Because the ice sheets also reduced the amount of carbon stored on land, the missing carbon must have been stored away in the ocean. It remained unclear for many decades what processes were responsible for this massive reorganization of the global carbon cycle during glacial periods, but scientists suspected that the Southern Ocean likely played an important role, due to two unique features. First, the densest, and therefore deepest type of water in the ocean are formed near Antarctica, appropriately named “Antarctic Bottom Water”. Second, it is the only place where deep ocean waters can move freely to the surface due to the action of winds. As a result, “Processes that occur on the surface in the Southern Ocean have a profound effect on the deep ocean and the amount of carbon that is stored there,” explains Dr. Karl Stein, ICCP scientist and lead author of the study.

Continue reading at Institute for Basic Science

Image via Institute for Basic Science