On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9 earthquake struck under the seabed off Japan—the most powerful quake to hit the country in modern times, and the fourth most powerful in the world since modern record keeping began. It generated a series of tsunami waves that reached an extraordinary 125 to 130 feet high in places. The waves devastated much of Japan’s populous coastline, caused three nuclear reactors to melt down, and killed close to 20,000 people.

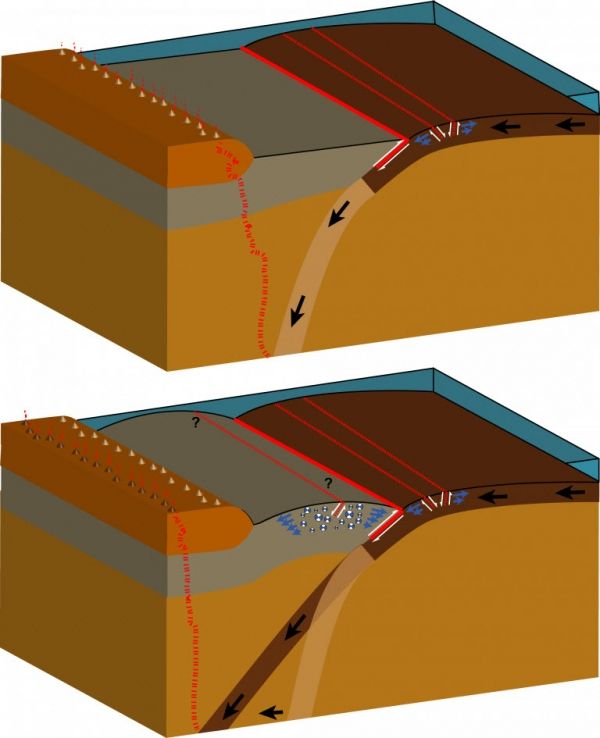

The tsunami’s obvious cause: the quake occurred in a subduction zone, where the tectonic plate underlying the Pacific Ocean was trying to slide under the adjoining continental plate holding up Japan and other landmasses. The plates had been largely stuck against each other for centuries, and pressure built up. Finally, something gave. Hundreds of square miles of seafloor suddenly lurched horizontally some 160 feet, and thrust upward by up to 33 feet. Scientists call this a megathrust. Like a hand waved vigorously underwater in a bathtub, the lurch propagated to the sea surface and translated into waves. As they approached shallow coastal waters, their energy concentrated, and they grew in height. The rest is history.

But scientists soon realized that something did not add up. Tsunami sizes tend to mirror earthquake magnitudes on a predictable scale; This one produced waves three or four times bigger than expected. Just months later, Japanese scientists identified another, highly unusual fault some 30 miles closer to shore that seemed to have moved in tandem with the megathrust. This fault, they reasoned, could have magnified the tsunami. But exactly how it came to develop there, they could not say. Now, a new study in the journal Nature Geoscience gives an answer, and possible insight into other areas at risk of outsize tsunamis.

Continue reading at Columbia University Earth Institute

Image via Columbia University Earth Institute