A new study shows that “hotspots” of nutrients surrounding phytoplankton — which are tiny marine algae producing approximately half of the oxygen we breathe every day — play an outsized role in the release of a gas involved in cloud formation and climate regulation.

The new research quantifies the way specific marine bacteria process a key chemical called dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), which is produced in enormous amounts by phytoplankton. This chemical plays a pivotal role in the way sulfur and carbon get consumed by microorganisms in the ocean and released into the atmosphere.

The work is reported today in the journal Nature Communications, in a paper by MIT graduate student Cherry Gao, former MIT professor of civil and environmental engineering Roman Stocker (now a professor at ETH Zurich, in Switzerland), in collaboration with Jean-Baptiste Raina and Professor Justin Seymour of University of Technology Sydney in Australia, and four others.

More than a billion tons of DMSP is produced annually by microorganisms in the oceans, accounting for 10 percent of the carbon that gets taken up by phytoplankton — a major “sink” for carbon dioxide, without which the greenhouse gas would be building up even faster in the atmosphere. But exactly how this compound gets processed and how its different chemical pathways figure into global carbon and sulfur cycles had not been well-understood until now, Gao says.

Read more at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

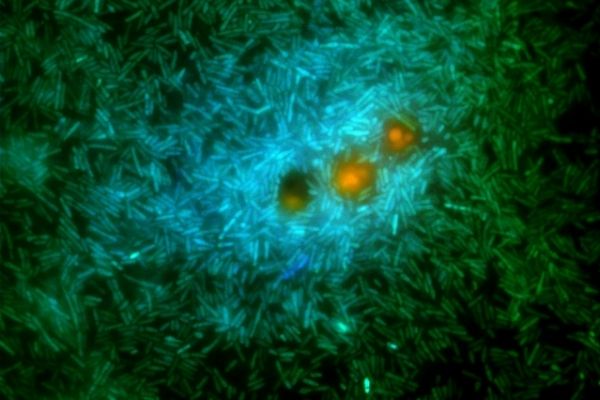

Image: A glimpse into the microscale world in the ocean: marine bacteria (green and cyan) feed on nutrients exuding from a genetically modified phytoplankton (orange). These bacteria release a substance called DMS that contributes to cloud formation. (Credit: Cherry Gao, Roman Stocker)