For 30 years, MBARI ecologist Ken Smith and his colleagues have studied deep-sea communities at a research site called Station M, located 4,000 meters (2.5 miles) below the ocean’s surface and 290 kilometers (180 miles) off the coast of Central California. A recent special issue of the journal Deep-Sea Research II features 16 new papers about research at Station M by scientists from around the world. These papers cover a wide range of topics, from satellite observations of the sea surface to the behavior and genetics of deep-sea life.

The deep seafloor is one of the largest and least known habitats on this planet. The flat, muddy expanses of the deep ocean floor—known as the abyssal plain—cover more than 50 percent of Earth’s surface and play a critical role in the Earth’s carbon cycle. Scientists visit from time to time, but they rarely get to stay long. That’s one reason why the long-term studies at Station M are so remarkable.

Animals on the deep seafloor get most of their food from the sunlit surface waters thousands of meters above. This food typically arrives in the form of marine snow—bits and pieces of dead algae or animals that sink to the muddy ocean bottom. This detritus carries carbon from the surface waters to the deep sea.

Read more at: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

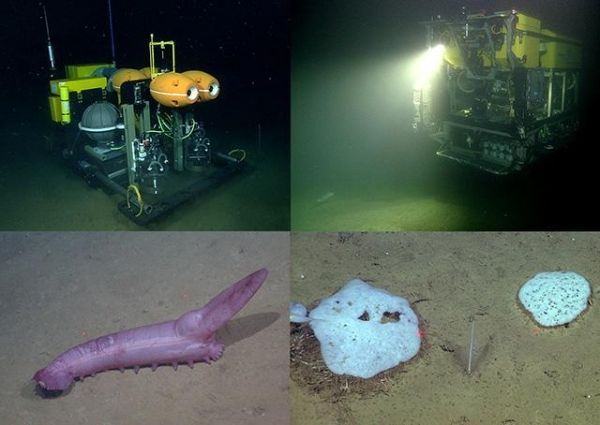

MBARI scientists use the Benthic Rover (top left) and ROV Doc Ricketts (top right) to study animal communities at Station M. Some of the seafloor animals living in the area include large sea cucumbers in the genus Psychropotes (bottom left), sponges, and a sea pen (bottom right). (Photo Credit © MBARI)