Rice University engineers have created a light-powered catalyst that can break the strong chemical bonds in fluorocarbons, a group of synthetic materials that includes persistent environmental pollutants.

In a study published this month in Nature Catalysis, Rice nanophotonics pioneer Naomi Halas and collaborators at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) and Princeton University showed that tiny spheres of aluminum dotted with specks of palladium could break carbon-fluorine (C-F) bonds via a catalytic process known as hydrodefluorination in which a fluorine atom is replaced by an atom of hydrogen.

The strength and stability of C-F bonds are behind some of the 20th century’s most recognizable chemical brands, including Teflon, Freon and Scotchgard. But the strength of those bonds can be problematic when fluorocarbons get into the air, soil and water. Chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, for example, were banned by international treaty in the 1980s after they were found to be destroying Earth’s protective ozone layer, and other fluorocarbons were on the list of “forever chemicals” targeted by a 2001 treaty.

“The hardest part about remediating any of the fluorine-containing compounds is breaking the C-F bond; it requires a lot of energy,” said Halas, an engineer and chemist whose Laboratory for Nanophotonics (LANP) specializes in creating and studying nanoparticles that interact with light.

Read more at Rice University

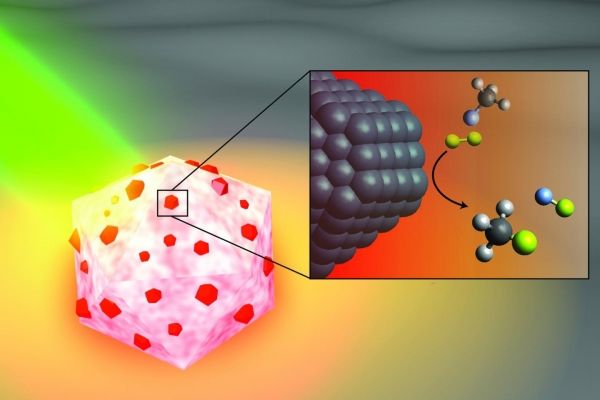

Image: An artist's illustration of the light-activated antenna-reactor catalyst Rice University engineers designed to break carbon-fluorine bonds in fluorocarbons. The aluminum portion of the particle (white and pink) captures energy from light (green), activating islands of palladium catalysts (red). In the inset, fluoromethane molecules (top) comprised of one carbon atom (black), three hydrogen atoms (grey) and one fluorine atom (light blue) react with deuterium (yellow) molecules near the palladium surface (black), cleaving the carbon-fluorine bond to produce deuterium fluoride (right) and monodeuterated methane (bottom). (Credit: H. Robatjazi/Rice University)