The shelves help slow interior glaciers’ slide toward the ocean, so if they were to fail, sea levels around the world could surge rapidly as a result. The study appears this week in the leading journal Nature.

Ice shelves are giant tongues of ice floating on the ocean around the edges of the continent. The vast land-bound glaciers behind them are constantly pushing seaward. But because many shelves are largely confined within expansive bays and gulfs, they are compressed from the sides and slow the glaciers’ march—somewhat like a person in a narrow hallway bracing their arms against the walls to slow someone trying to push past them. But ice shelves experience a competing stress: they stretch out as they approach the ocean. Satellite observations show that, as a result, they rip apart; most are raked with numerous long fractures perpendicular to the direction of stretching. Fractures that form at the surface can be tens of meters deep; others, forming from the bottom, can penetrate the ice hundreds of meters upward. Some fractures are hundreds of meters wide.

Currently, most of the shelves are frozen year round, and stable. But scientists project that widespread warming could occur later in the century.

Continue reading at Columbia University Earth Institute

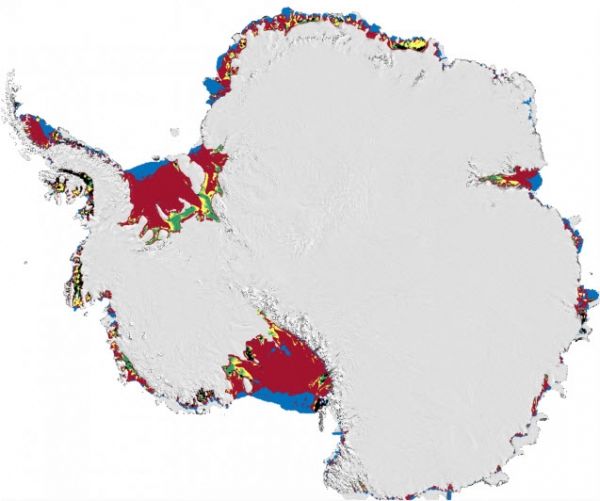

Image via Columbia University Earth Institute