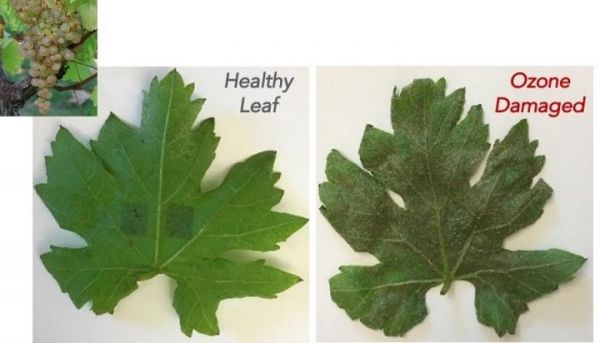

Farmers and fruit growers are reporting that climate change is leading to increased ozone concentrations on the soil surface in their fields and orchards – an exposure that can cause irreversible plant damage, reduce crop yields and threaten the food supply, say materials chemists led by Trisha Andrew at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Writing in Science Advances, co-first authors Jae Joon Kim and Ruolan Fan show that the Andrew lab’s method of vapor-depositing conducting polymer “tattoos” on plant leaves can allow growers to accurately detect and measure such ozone damage, even at low exposure levels. Their resilient polymer tattoos placed on the leaves allow for “frequent and long-term monitoring of cellular ozone damage in economically important crops such as grapes and apples,” Andrew says.

They write, “We selected grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) as our model plant because the fruit yield and fruit quality of grapevines decrease significantly upon exposure to ground level ozone, leading to significant economic losses.” Ground-level ozone can be produced by the interaction between the nitrates in fertilizer and the sun, for example.

Read more at: University of Massachusetts Amherst

Vapor-depositing conducting polymer "tattoos" on plant leaves can allow growers to accurately detect and measure such ozone damage, even at low exposure levels. UMass Amherst materials chemists say their conducting polymer film, PEDOT, is just 1 micron thick so it lets sunlight in and does not hurt leaves. (Photo Credit: UMass Amherst/Andrew lab)