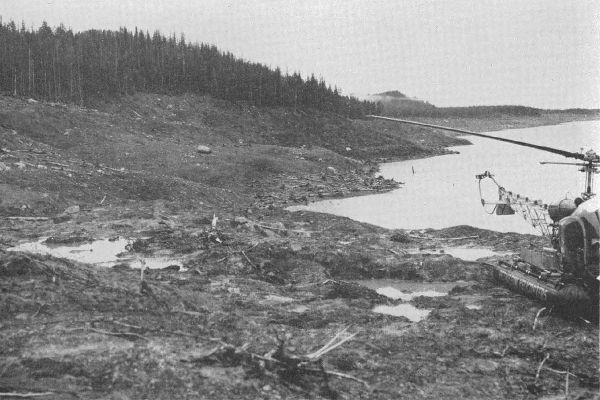

Just over 60 years ago, a giant wave washed over the narrow inlet of Lituya Bay, Alaska, knocking down the forest, sinking two fishing boats and claiming two lives.

A nearby earthquake had triggered a rockslide into the bay, suddenly displacing massive volumes of water. The large landslide tsunami reached a height of more than 160 metres and caused a run-up (the vertical height that a wave reaches up a slope) of 524 metres above sea level. For perspective, imagine run-up to about the height of the CN Tower in Toronto (553 metres) or One World Trade Center in New York City (541 metres).

Large landslides, like the one that hit Lituya Bay in 1958, are mixtures of rock, soil and water that can move very quickly. When a landslide hits a body of water, it can generate waves, especially in mountainous coastal areas, where steep slopes meet a fiord, lake or reservoir. Although mega-tsunamis are often sensationalized in the news, real and scientifically documented events motivate new research.

In late July, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake near Perryville, Alaska, triggered a tsunami warning for south Alaska, the Aleutian Islands and the Alaskan Peninsula. And scientists recently warned that a retreating glacier in a fiord in Prince William Sound, Alaska, had elevated the risk of a landslide and tsunami in a popular fishing and tourism area not far from the town of Whittier.

Continue reading at Queen's University.

Image via Alaska Earthquake Center.