There are fossils, found in ancient marine sediments and made up of no more than a few magnetic nanoparticles, that can tell us a whole lot about the climate of the past, especially episodes of abrupt global warming. Now, researchers including doctoral student Courtney Wagner and associate professor Peter Lippert from the University of Utah, have found a way to glean the valuable information in those fossils without having to crush the scarce samples into a fine powder. Their results are published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“It’s so fun to be a part of a discovery like this, something that can be used by other researchers studying magnetofossils and intervals of planetary change,” Wagner says. “This work can be used by many other scientists, within and outside our specialized community. This is very exciting and fulfilling.”

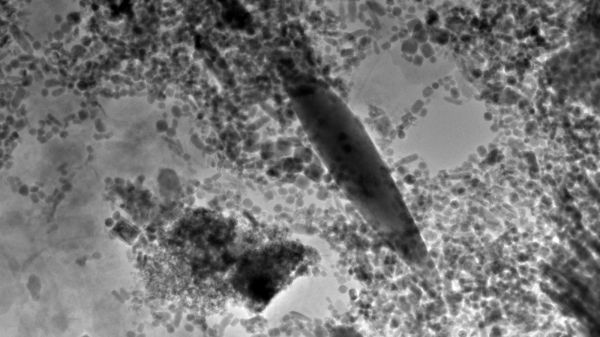

The name “magnetofossil” may bring to mind images of the X-Men, but the reality is that magnetofossils are microscopic bacterial iron fossils.

Continue reading at University of Utah

Image via University of Utah