A new study published Feb. 24 in the journal Royal Society Open Science documents the earliest-known fossil evidence of primates.

A team of 10 researchers from across the U.S. analyzed several fossils of Purgatorius, the oldest genus in a group of the earliest-known primates called plesiadapiforms. These ancient mammals were small-bodied and ate specialized diets of insects and fruits that varied by species. These newly described specimens are central to understanding primate ancestry and paint a picture of how life on land recovered after the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago that wiped out all dinosaurs — except for birds — and led to the rise of mammals.

Gregory Wilson Mantilla, a University of Washington professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the UW’s Burke Museum of Natural History & Culture, co-led the study with Stephen Chester of Brooklyn College and the City University of New York. The team analyzed fossilized teeth found in the Hell Creek area of northeastern Montana. The fossils, which are now part of the collections at the University of California Museum of Paleontology, are estimated to be 65.9 million years old, about 105,000 to 139,000 years after the mass extinction event. Based on the age of the fossils, the team estimates that the ancestor of all primates —including plesiadapiforms and today’s primates such as lemurs, monkeys and apes — likely emerged by the Late Cretaceous and lived alongside large dinosaurs.

Read more at: University of Washington

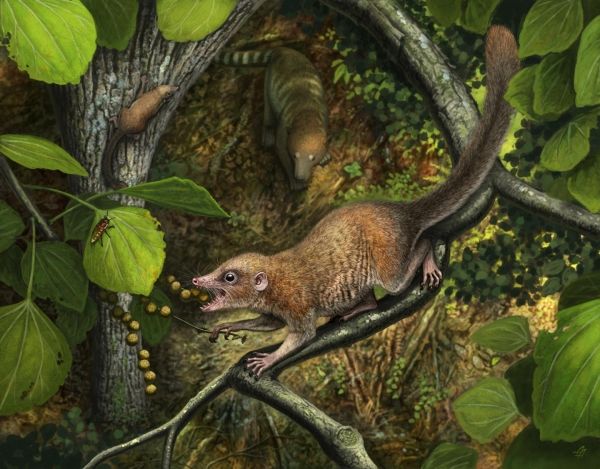

Shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs, the earliest known archaic primates, such as the newly described species Purgatorius mckeeveri shown in the foreground, quickly set themselves apart from their competition -- like the archaic ungulate mammal on the forest floor -- by specializing in an omnivorous diet including fruit found up in the trees. (Photo Credit: Andrey Atuchin)