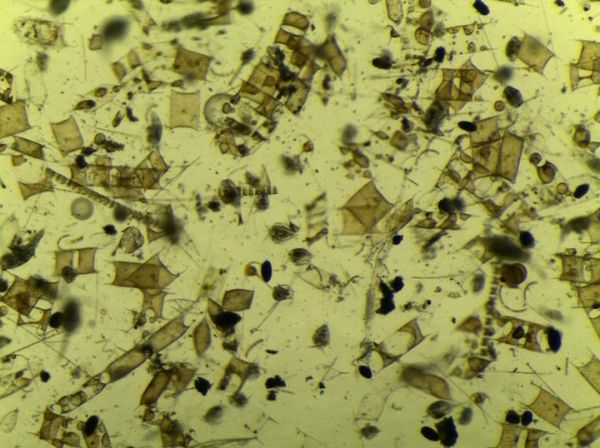

The annually occurring algal spring blooms play an important role for our climate, as they remove large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. However, they are an ephemeral phenomenon. Most of the carbon is released into the water once the algae die. There, bacteria are already waiting to finish them off and consume the algal remains.

Previous studies have shown that in these blooms, different algae can come out on top each year. However, within the bacteria subsequently degrading the algae, the same specialised groups prevail year after year. Apparently not the algae themselves but rather their components - above all chains of sugar molecules, the so-called polysaccharides - determine which bacteria will thrive. However, the details of the bacterial response to the algal feast are still not fully understood.

Metaproteomics: Studying bacterial proteins in bulk

Therefore, Ben Francis together with colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, the University of Greifswald and the MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen now took a closer look at the bacterial insides. "We decided to center on a method called metaproteomics, which involves studying all proteins in a microbial community, in our case in the seawater", Francis explains. "In particular, we looked at transporter proteins, whose activity is critical in understanding the uptake of algal sugars into bacterial cells." In the metaproteomic data, the scientists saw that these transporter proteins distinctly changed over time. "We saw a pronounced shift in the abundance of transporter proteins predicted to be involved in uptake of different types of polysaccharide", Francis continues. "This indicates that the bacteria start off by mostly focusing on the 'easy to degrade' substrates, such as laminarin and starch. Then later on they move on and attack the 'harder to degrade' polymers composed of mannose and xylose."

Read more at Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology

Image: Seasonal blooms of tiny algae play an important role in marine carbon cycling. Now a new detail of the surrounding mysteries has been uncovered. (Credit: Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology / G. Reintjes)