If you were to visit the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau a thousand years ago, you’d find conditions remarkably familiar to the present. The climate was warm, but drier than today. There were large populations of Indigenous people known as the Fremont, who hunted and grew crops in the area. With similar climate and moderate human activity, you might expect to see the types of wildfires that are now common to the American West: infrequent, gigantic and devastating. But you’d be wrong.

In a new study led by the University of Utah, researchers found that the Fremont used small, frequent fires, a practice known as cultural burning, which reduced the risk for large-scale wildfire activity in mountain environments on the Fish Lake Plateau—even during periods of drought more extreme and prolonged than today.

Read more at: University of Utah

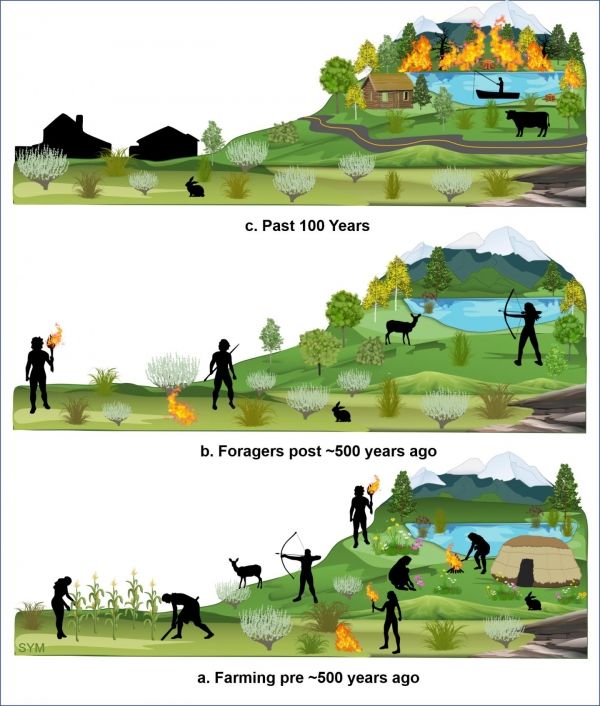

A schematic of what the authors think the landscape and human activity was like over the last 1,200 years in the Fish Lake Plateau region. A) 1,200 to 500 years ago, high density of people hunting, harvesting wild plants and cultivating crops. They controlled the fire regime with cultural burning that created a landscape dominated by the plants for sustenance rather than dense forest typical of the elevation. B) 500-100 years ago, farming activity ceased abrupt. Forgers and hunters still practiced cultural burning, although much less than farmers had previously. Trees began to slowly expand their range. C) Past 100 years, European settlers made cultural burning illegal, and the landscape became dominated by forests, setting up conditions for catastrophic wildfires. (Photo Credit: S. Yoshi Maezumi)