The bulging, equator-belted midsection of Earth currently teems with a greater diversity of life than anywhere else — a biodiversity that generally wanes when moving from the tropics to the mid-latitudes and the mid-latitudes to the poles.

As well-accepted as that gradient is, ecologists continue to grapple with the primary reasons for it. New research from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Yale University and Stanford University suggests that temperature can largely explain why the greatest variety of aquatic life resides in the tropics — but also why it has not always and, amid record-fast global warming, soon may not again.

Published May 6 in the journal Current Biology, the study estimates that marine biodiversity tends to increase until the average surface temperature of the ocean reaches about 65 degrees Fahrenheit, beyond which that diversity slowly declines.

During intervals of Earth’s history when the maximum surface temperature was lower than 80 degrees Fahrenheit, the greatest biodiversity was found around the equator, the study concluded. But when that maximum exceeded 80 degrees, marine biodiversity ebbed in the tropics, where those highest temperatures would have manifested, while peaking in waters at the mid-latitudes and the poles.

Read more at University of Nebraska-Lincoln

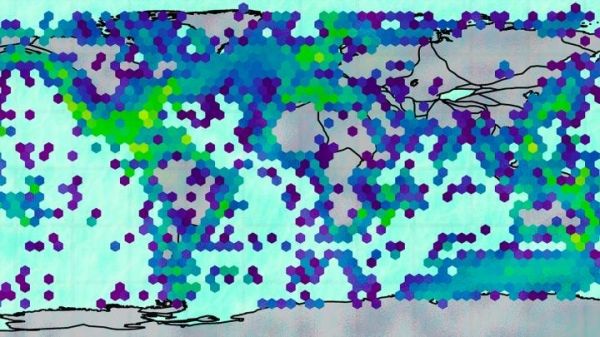

Image: A map illustrating the occurrence of mollusks in marine shelf environments between 1700 and 2020, with darker hexagons indicating fewer and lighter indicating more. By compiling and analyzing mollusk fossil data from the past 145 million years, Nebraska's Will Gearty and colleagues have shown that temperature largely explains the diversity of aquatic life in the tropics. Human-driven global warming is expected to reduce that tropical biodiversity in coming centuries. (Credit: Adapted from figure in Current Biology / Cell Press)