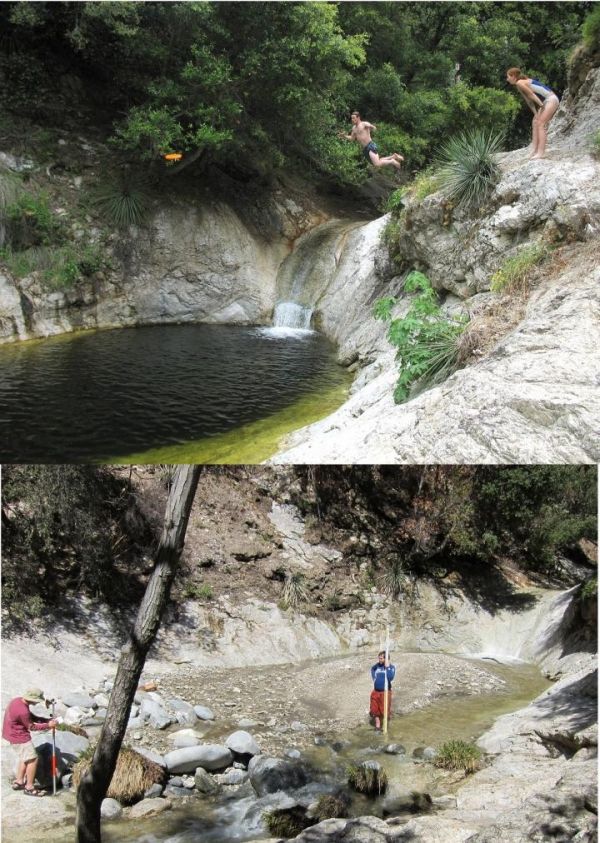

Deep pools below waterfalls are popular recreational swimming spots, but sometimes they can be partially or completely filled with sediment. New research showed how and why pools at the base of waterfalls, known as plunge pools, go through natural cycles of sediment fill and evacuation. Beyond impacting your favorite swimming hole, plunge pools also serve important ecologic and geologic functions. Deep pools are refuges for fish and other aquatic animals in summer months when water temperatures in shallow rivers can reach lethal levels. Waterfalls also can liquefy sediment within the pool, potentially triggering debris flows that can damage property and threaten lives. Over geologic time, pools are importance because the energetic waterfall jet can erode the rock walls of the pool—slowly moving the waterfall upstream, while simultaneously creating a deep canyon in its wake.

Reporting in the journal Geology today, Joel Scheingross of the University of Nevada Reno, and Michael Lamb of the California Institute of Technology, provided a new theoretical framework to predict when plunge pools fill with sediment, and when they subsequently evacuate that sediment exposing the rock walls of the pool to erosion. They showed that waterfall plunge pools tend to fill with sediment during modest river floods when sediment is transported in the reach upstream of the waterfall, but the waterfall jet is too weak to move all the sediment it receives from upstream. In contrast, during large floods, a strong waterfall jet can more efficiently move sediment up and out of the pool, outpacing the delivery of sediment from upstream, and exposing bedrock to erosion.

Read more at Geological Society of America

Image: Example of sediment filling and evacuation of sediment in a small waterfall plunge pool on Arroyo Seco, San Gabriel Mountains, California. Top: Plunge pool, free of sediment, in June 2006 with swimmer leaping. Bottom: The same plunge pool filled with sediment in March 2010 following a wildfire in 2009 that overwhelmed the pool with sediment. (Credit: Top photo credit: Kelin X. Whipple, bottom photo credit: Michael P. Lamb.)