One of the most important and widespread reef-building corals, known as cauliflower coral, exhibits strong partnerships with certain species of symbiotic algae, and these relationships have persisted through periods of intense climate fluctuations over the last 1.5 million years, according to a new study led by researchers at Penn State. The findings suggest that these corals and their symbiotic algae may have the capacity to adjust to modern-day increases in ocean warming, at least over the coming decades.

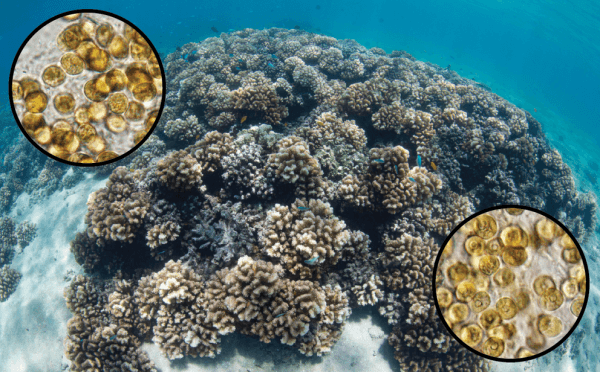

Cauliflower corals — which are in the genus Pocillopora — are branching corals that provide critical habitat for one-quarter of the world’s fish and many kinds of invertebrates, such as lobsters, sea urchins and giant clams. They are common throughout the Indo-Pacific — the region extending from eastern Africa, north to India and Southeast Asia, across Australia and encompassing Hawaii — and are capable of long-range dispersal and rapid growth, making them among the first species to repopulate reefs damaged by typhoons and events of mass coral bleaching and mortality.

“We found that Pocillopora has maintained a close relationship with certain species of algae in the genus Cladocopium over repeated oscillations in Earth’s climate,” said Todd LaJeunesse, professor of biology, Penn State. “Our findings reinforce how stable and resilient these relationships are over deep time.”

Read more at: Penn State

A community of Pocillopora corals on a reef in Palau with light micrograph insets of Cladocopium pacificum nov. (left) and Cladocopium latusorum sp. nov. (right), two dinoflagellate symbionts critical to these coral animals' health and growth. (Photo Credit: Coral Photo, Tom Bridge, James Cook University; Algae Photos, Kira Turnham, Penn State)