The surface of the sun churns with energy and frequently ejects masses of highly-magnetized plasma towards Earth. Sometimes these ejections are strong enough to crash through the magnetosphere — the natural magnetic shield that protects the Earth — damaging satellites or electrical grids. Such space weather events can be catastrophic.

Astronomers have studied the sun's activity for centuries with greater and greater understanding. Today, computers are central to the quest to understand the sun's behavior and its role in space weather events.

The bipartisan PROSWIFT (Promoting Research and Observations of Space Weather to Improve the Forecasting of Tomorrow) Act, passed into law in October 2020, is formalizing the need to develop better space weather forecasting tools.

"Space weather requires a real-time product so we can predict impacts before an event, not just afterward," explained Nikolai Pogorelov, distinguished professor of Space Science at The University of Alabama in Huntsville, who has been using computers to study space weather for decades. "This subject – related to national space programs, environmental, and other issues – was recently escalated to a higher level."

Read more at University of Texas at Austin, Texas Advanced Computing Center

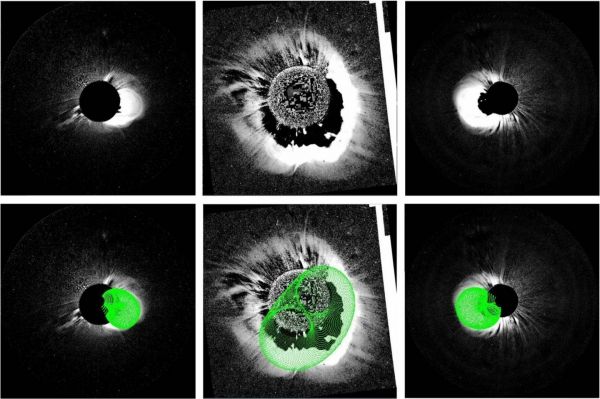

Image: (Top panel, from left to right) July 12, 2012 coronal mass ejection seen in STEREO B Cor2, SOHO C2, and STEREO A Cor2 coronagraphs, respectively. (Bottom panel) The same images overlapped with the model results. (Credit: Talwinder Singh, Mehmet S. Yalim, Nikolai V. Pogorelov, and Nat Gopalswamy)