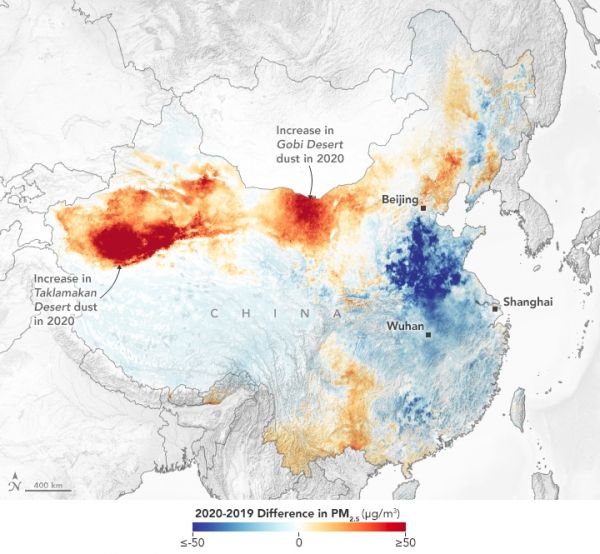

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, it became clear from satellite observations and human experience that the world’s air grew cleaner. But new research shows that not all pollutants were taken out of circulation during societal lockdowns. In particular, the concentration of tiny airborne pollution particles known as PM2.5 did not change that much because natural variability in weather patterns dominated and mostly obscured the reduction from human activity.

“Intuitively you would think that if there is a major lockdown situation, we would see dramatic changes, but we didn’t,” said Melanie Hammer, a visiting research associate at Washington University in St. Louis and leader of the study. “It was kind of a surprise that the effects on PM2.5 were modest.”

PM2.5 describes particles, produced by both human activities and natural processes, that are smaller than 2.5 micrometers, or roughly 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair. PM2.5 is small enough to linger in the atmosphere and, when inhaled, is associated with increased risk of heart attack, cancer, asthma, and a host of other human health effects. “We were most interested in looking at changes in PM2.5 because it is the leading environmental risk factor for premature mortality globally,” Hammer said.

Continue reading at NASA Earth Observatory

Image via NASA Earth Observatory