How can snow cover on the Himalayas influence the species that thrive in the Arabian Sea? How could changes in wind speed and humidity lead to food and national security concerns a thousand kilometers away? Joaquim Goes, Helga do Rosario Gomes, and colleagues on two continents have spent the past two decades trying to decode these riddles.

The story begins in the early 2000s, around the time that NASA’s Aqua satellite was launched. Goes, a specialist in remote sensing of the ocean, was examining data from SeaWiFS and Aqua. He was focused on chlorophyll-a, a pigment used by ocean phytoplankton (and plants worldwide) to harness sunlight and turn it into food energy. He was focusing on observations of phytoplankton populations in the Arabian Sea during the summer monsoon, but by chance he looked at winter data. There was far more chlorophyll-a than anyone should reasonably expect.

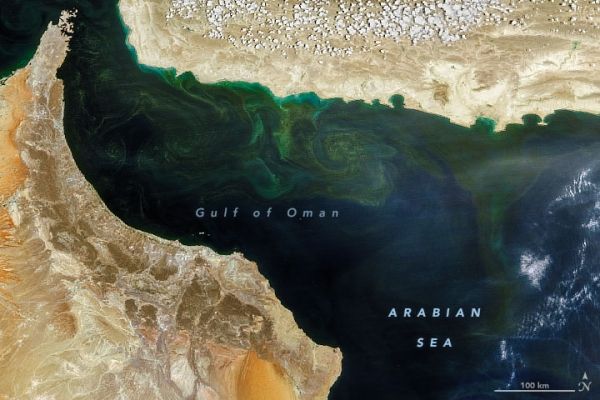

At first Goes thought it was an error. But over the next decade, reports of increasing algae and decreasing fish catches came in from colleagues in southern Asia. Goes and Gomes made several sea-going expeditions and saw it for themselves: The Arabian Sea was teeming with Noctiluca scintillans, an organism that was scarcely reported in the region during previous winters.

Continue reading at NASA Earth Observatory

Image via NASA Earth Observatory