City dwellers seldom experience the near-reverence of watching deer walk through their yards, both for a lack of deer and, often, a lack of a yard. In cities, not everyone has the same experiences with nature. That means that the positive effects of those experiences—such as mental health benefits—and the negative effects—such as vehicle strikes—are unequally distributed. Urban ecologists have proposed that income and biodiversity may be related, such that a so-called “luxury effect” may lead to more biodiversity in landscaped, affluent suburban neighborhoods.

New research, however, published in Global Change Biology, suggests that while there is an association between income and diversity of medium to large mammals, another factor is stronger: “urban intensity,” or the degree to which wild lands have been converted to densely-populated, paved-over grey cities.

“Wildlife have all sorts of interactions with people, both positive and negative,” says Seth Magle, director of the Urban Wildlife Institute at Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago. “So finding that wildlife are distributed unequally in different types of neighborhoods also means these benefits and costs are not equally shared. Cities are a form of nature, but that nature is not the same block-by-block, which has profound effects on the people who live on those blocks.”

Read more at: University of Utah

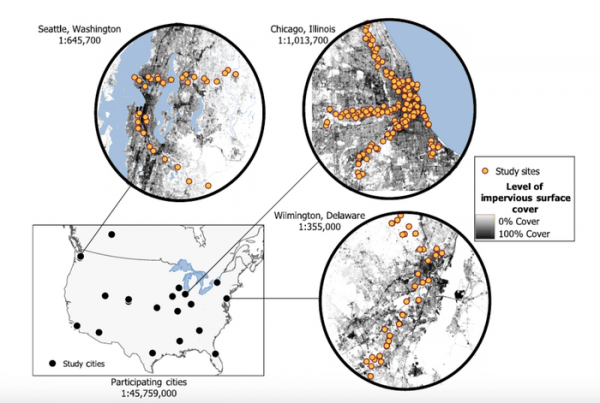

Map of the distribution of the 20 cities across North America that contributed data for this analysis as well as three representative examples of the distribution of camera trapping study sites along each city’s respective urbanization gradient. Points for Tacoma, Washington and Seattle, Washington are partially overlapping, as are points for Denver, Colorado and Fort Collins, Colorado. (Photo Credit: UWIN)