As rising sea levels threaten coastal areas, scientists are using an emerging nuclear dating technique to track the ins and outs of water flow.

Florida is known for water. Between its beaches, swamps, storms and humidity, the state is soaked. And below its entire surface lies the largest freshwater aquifer in the nation.

The Floridan Aquifer produces 1.2 trillion gallons of water each year — that’s almost 2 million Olympic-sized swimming pools. It serves as a primary source of drinking water for over 10 million people and supports the irrigation of over 2 million acres. It also supplies thousands of lakes, springs and wetlands, and the environments they nurture.

But as glaciers melt due to global warming, rising sea levels threaten this water source — and other coastal aquifers — with the intrusion of saltwater. It’s more crucial than ever to study the history and behavior of water in these aquifers, and Florida’s dynamic water systems make it a prime testbed.

Read more at DOE/Argonne National Laboratory

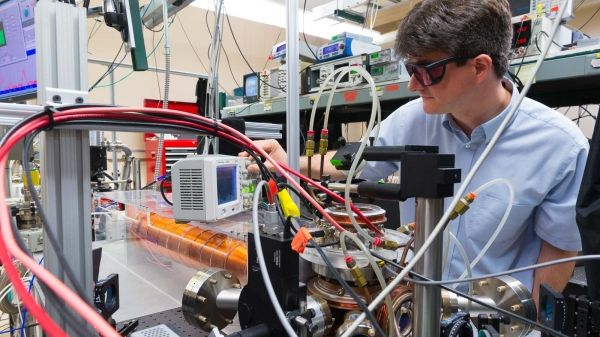

Image: Argonne scientist Peter Mueller at the TRACER Center. The facility has advanced the science of krypton dating for young and ancient groundwater and glacial ice. (Image credit: Argonne National Laboratory.)