The Late Devonian mass extinction (roughly 372 million years ago) was one of five mass extinctions in Earth’s history, with roughly 75% of all species disappearing over its course. It happened in two “pulses,” spaced about 800,000 years apart, with most of the extinctions happening in the second pulse. However, for one group of animals living in eastern North America, the first pulse dealt the deadlier blow.

Research out today in Scientific Reports looks at how and why this group of animals, called brachiopods, seemed to do the opposite of so many other species. What caused this group to hit the accelerator toward extinction?

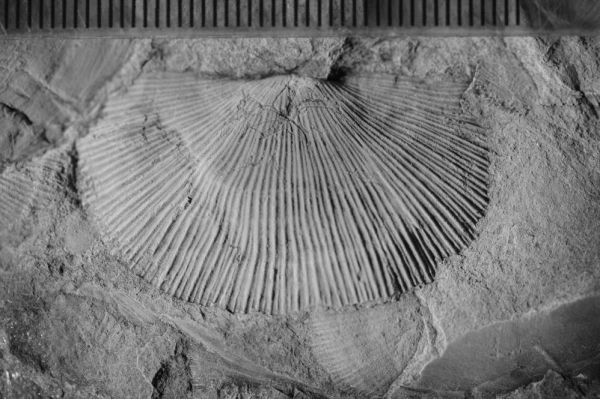

Brachiopods are small, shelled, filter-feeding ocean dwellers that are extremely abundant and well-preserved in the fossil record, says researcher Jaleigh Pier ’18 (CLAS), now a Ph.D. student in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Cornell University. These qualities make brachiopods ideal for studying disturbances, like mass extinctions, from the deep past.

Continue reading at University of Connecticut

Image via University of Connecticut