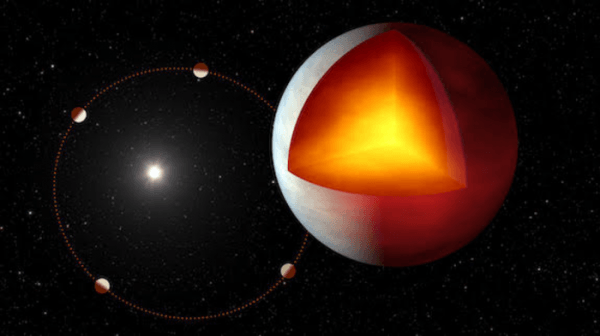

Imagine being in a place where the winds are so strong that they move at the speed of sound. That’s just one aspect of the atmosphere on XO-3b, one of a class of exoplanets (planets outside our solar system), known as hot Jupiters. The eccentric orbit of the planet also leads to seasonal variations hundreds of times stronger than what we experience on Earth. In a recent paper, a McGill-led research team, provides new insight into what seasons looks like on a planet outside our solar system. The researchers also suggest that the oval orbit, extremely high surface temperatures (2,000 degrees C- hot enough to vaporize rock) and “puffiness” of XO-3b reveal traces of the planet’s history. The findings will potentially advance both the scientific understanding of how exoplanets form and evolve and give some context for planets in our own solar system.

Hot Jupiters are massive, gaseous worlds like Jupiter, that orbit closer to their parent stars than Mercury is to the Sun. Though not present in our own solar system, they appear to be common throughout the galaxy. Despite being the most studied type of exoplanet, major questions remain about how they form. Could there be subclasses of hot Jupiters with different formation stories? For example, do these planets take shape far from their parent stars – at a distance where it’s cold enough for molecules such as water to become solid – or closer. The first scenario fits better with theories about how planets in our own solar system are born, but what would drive these types of planets to migrate so close to their parent stars remains unclear.

To test those ideas, the authors of a recent McGill-led study used data from NASA’s retired Spitzer Space Telescope to look at the atmosphere of exoplanet XO-3b. They observed eccentric seasons and measured wind speeds on the planet by obtaining a phase curve of the planet as it completed a full revolution about its host star.

Read more at McGill University

Image: Hot Jupiters are massive, gaseous worlds like Jupiter, that orbit closer to their parent stars than Mercury is to the Sun. In a recent paper, a McGill-led research team, provides new insight into what seasons looks like on a hot Jupiter. The researchers also suggest that the oval orbit, extremely high surface temperatures (2,000 degrees C- hot enough to vaporize rock) and “puffiness” of XO-3b reveal traces of the planet’s history. The findings will potentially advance both the scientific understanding of how exoplanets form and evolve and give some context for planets in our own solar system. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC))