One of the many serious consequences of the climate crisis is that precious permafrost is thawing, and this is unleashing even more carbon to the atmosphere and further exacerbating climate change. However, it’s complicated. For example, sometimes permafrost can thaw rapidly and scientists are unsure why and what these abrupt thaws mean in terms of feedback loops. This makes it difficult to predict the future impact on the climate. Thanks to an ESA–NASA initiative, new research digs deep into understanding the complexities of permafrost thaw and how carbon is released over time.

Permafrost is frozen soil, rock or sediment – sometimes hundreds of metres thick. To be classified as permafrost, the ground has to have been frozen for at least two years, but much of the subsurface in the polar regions has remained frozen since the ice age. Permafrost holds carbon-based remains of vegetation and animals that froze before decomposition could set in. Most of Earth’s permafrost is in the northern hemisphere – Arctic permafrost stores almost 1700 billion tonnes of carbon.

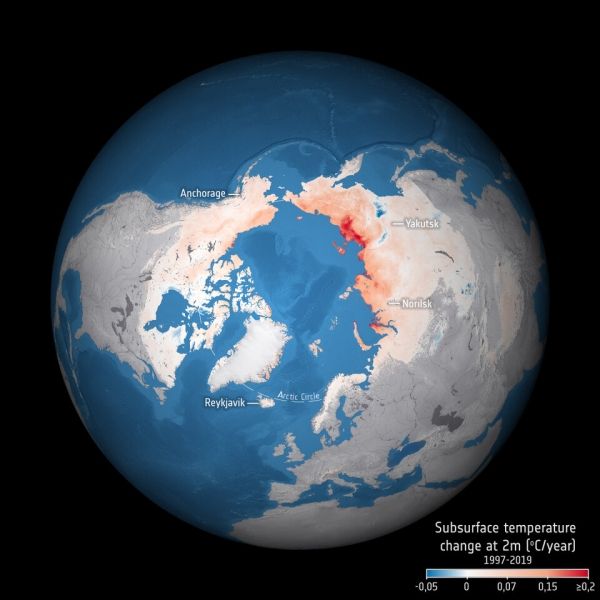

Permafrost plays a critical role in keeping our planet from losing its cool, but the rise in global temperatures, particularly evident in the Arctic, is causing the subsurface ground to thaw and release long-held carbon to the atmosphere.

Highlighting the importance of permafrost in the climate system, the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment recently featured a wealth of research papers in a special collection that examines the physical, biogeochemical and ecosystem changes related to permafrost thaw and the associated impacts.

Continue reading at European Space Agency

Image via European Space Agency