Some plants and patches of Earth withstand heat and dry spells better than others. A new Stanford University study shows those different coping mechanisms are closely linked to wildfire burn areas, posing increasing risks in an era of climate change.

The results, published Feb. 7 in Nature Ecology and Evolution, show swaths of forest and shrublands in most Western states likely face greater fire risks than previously predicted because of the way local ecosystems use water. Under the same parched conditions, more acreage tends to burn in these zones because of differences in at least a dozen plant and soil traits.

The study’s authors set out to test an often-repeated hypothesis that climate change is increasing wildfire hazard uniformly in the West. “I asked, is that true everywhere, all the time, for all the different kinds of vegetation? Our research shows it is not,” said lead author Krishna Rao, a PhD student in Earth system science.

The study arrives as the Biden administration prepares to launch a 10-year, multibillion-dollar effort to expand forest thinning and prescribed burns in 11 Western states.

Previous research has shown that climate change is driving up what scientists call the vapor pressure deficit, which is an indicator of how much moisture the air can suck out of soil and plants. Vapor pressure deficit has increased over the past 40 years across most of the American West, largely because warmer air can hold more water. This is a primary mechanism by which global warming is elevating wildfire hazards.

Read more at: Stanford University

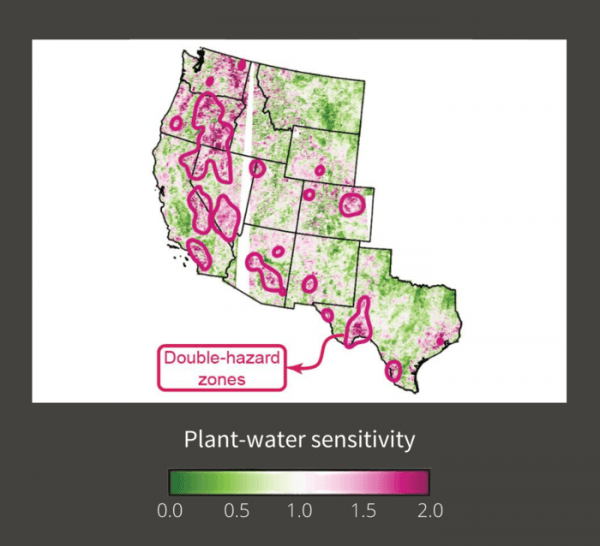

In 18 zones of the U.S. West, plant water sensitivity is high (>1.5), and the vapor pressure deficit is rising faster than average. Because both factors increase fire hazards, the overlaps are likely to amplify the effect of climate change on burned areas. (Photo Credit: Adapted from Rao et al, 2021, Nature Ecology and Evolution)